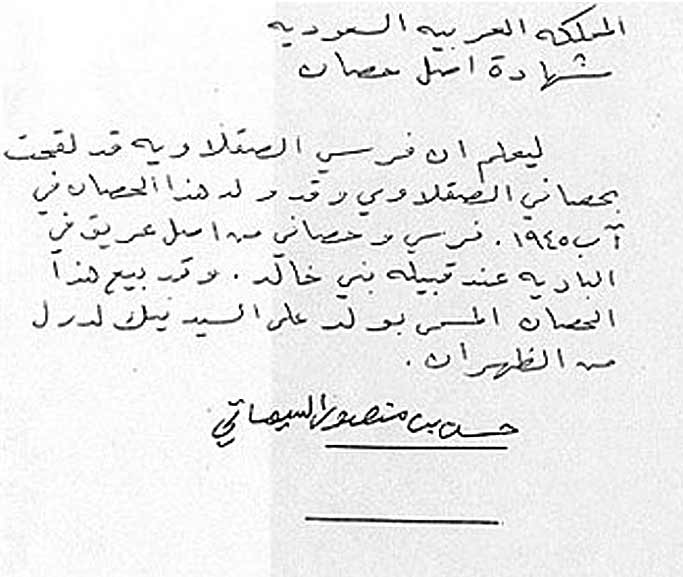

On the hujjah of the desert-bred stallion Walid El Seglawi

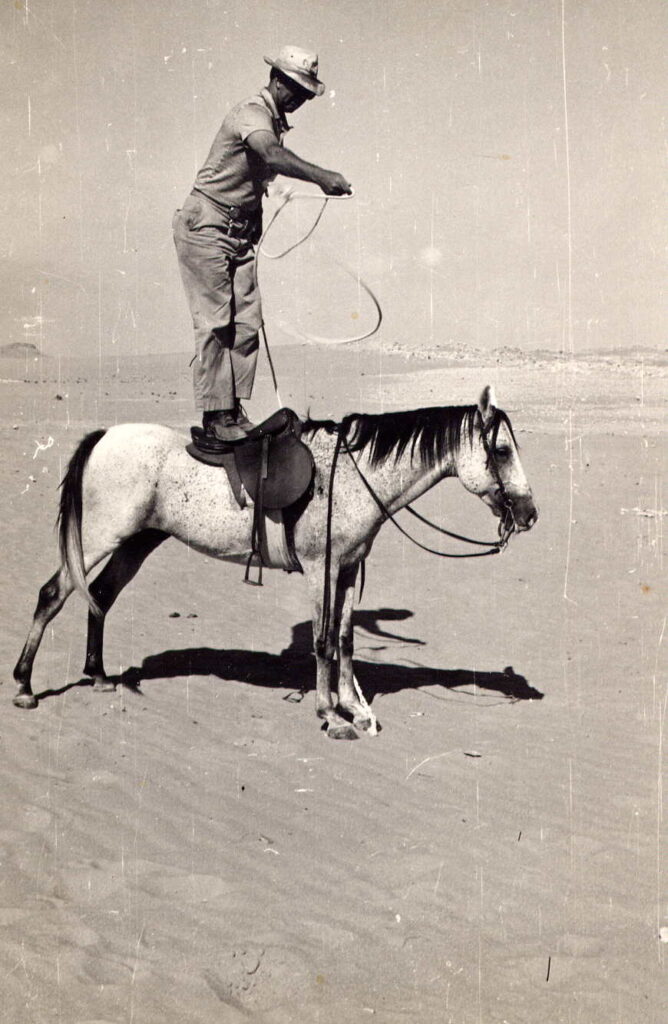

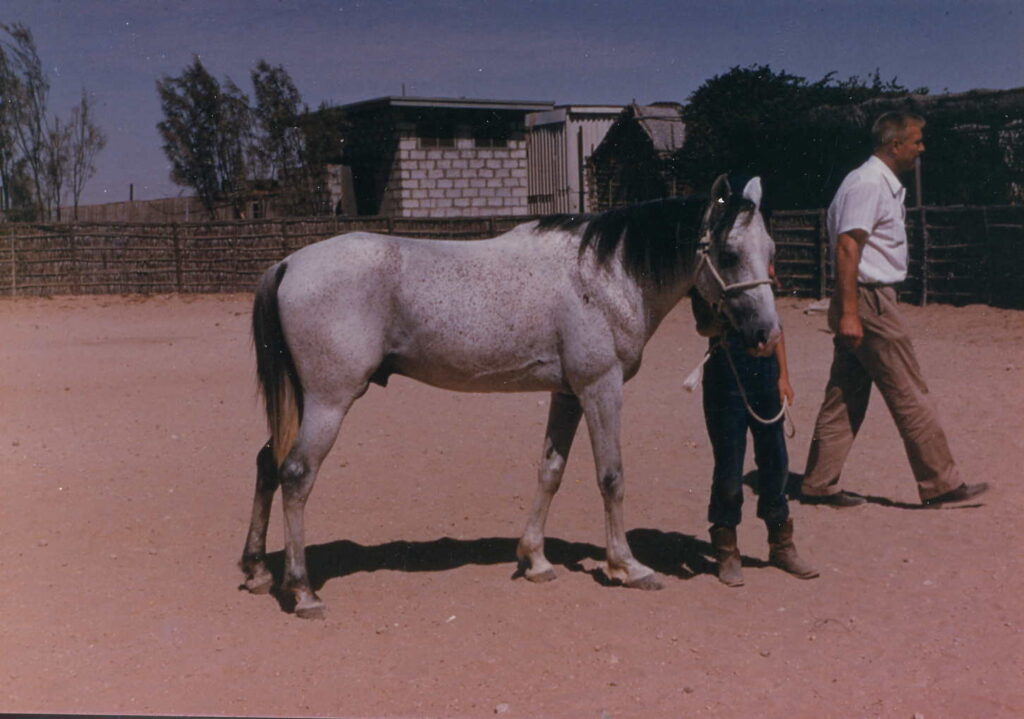

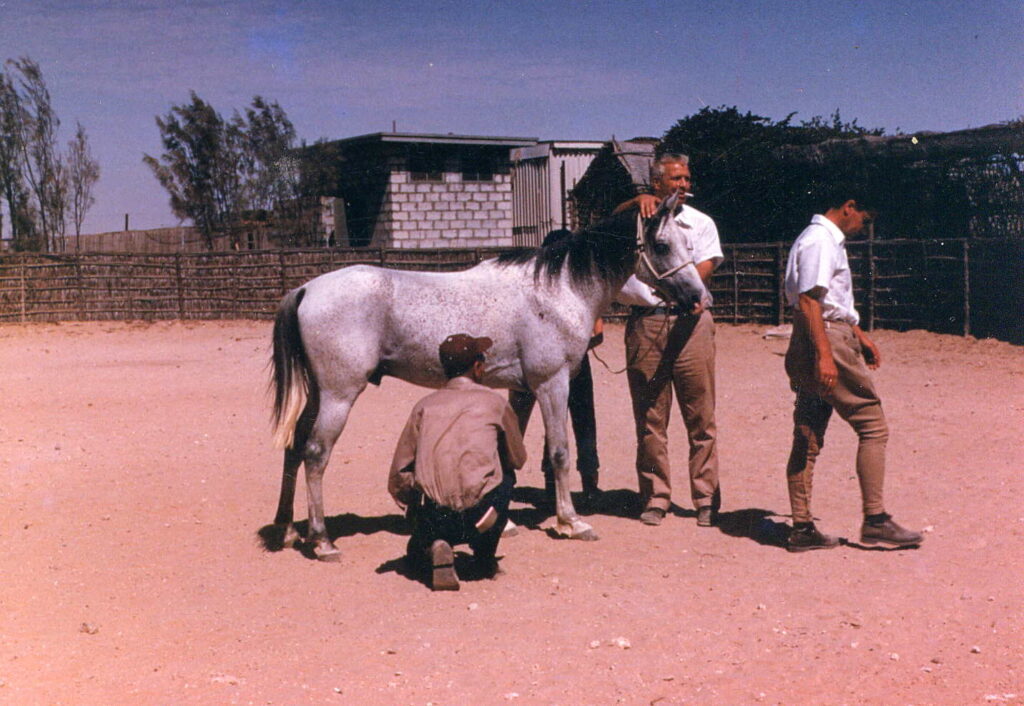

Hujaj (plural of hujjah), the Arabic authentication certificates, come in all shapes and forms. Some consist of a few handwritten words scribbled by the breeder or owner on a piece of paper. Some are more elaborate, the work of government officials, with dates, stamps, letterahead, and formal language. Some are the words of barely literate men, some are high literature. Look at this hujjah for the 1945 grey stallion Walid El Seglawi (his photos below), the sire of the mare Jamalah El Jedrani imported to the USA by ARAMCO expatriate Fran Richards. This is my translation of it:

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Testimony on the origin of a horse

Let it be known that my mare, the Saqlawiyah, was bred to my horse the Saqlawi, and that this horse was born in August 1945 [implied: as a result of the mating]. My mare and my horse are from a deep-rooted origin in the steppe [badiyah] with the tribe of Bani Khalid; and this horse, named Walid, was sold to Mr. Nick Lederle of al-Dhahran.

Hasan son of Mansur the Saihati

The document is straightforward, but there is more than meets the eye. A few observations on both text and context:

First, the handwriting and calligraphy. The body of the text was very clearly written by a different person that the person who wrote most of the name at the end. The “S” in Saihati in the name at the end is written with three “teeth”. The “S” in words in the main text like farasi (“my mare”), musamma (“named”), and sayyid (“Mr”), and in “Hasan” in the name at the end, are all written without the “teeth”. Also, the body of the document up to and including the first name “Hasan” are written in a flowing, confident handwriting, while the rest of the name, specifically the words “son of Mansur the Saihati” (and perhaps even the letter N in Hasan) are written with a different, more hesitant handwriting.

Even the calligraphy is different. Most of the document is in the calligraphy favored by Shami (i.e., Syrians broadly speaking, meaning Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians) and Iraqi people, while the words “son of Mansur the Saihati” is typical Khaliji (i.e., Gulfi) Arabic calligraphy. To me this is indicative of a text written by a Shami, (Syrian, Lebanese or Palestinian) or Iraqi employee of ARAMCO, while the name at the end, specifically the words “son of Mansur the Saihati” appear to have been written by Hasan son of Mansur the Saihati himself, a Saudi citizen from Saihat in Eastern Saudi Arabia. What probably happened — and this is admittedly speculative — is that the scribe was about to write the full name of the owner/seller in the scribe’s own hand, then stopped (or was made to stop by someone else — “no, let him sign!”) and let the owner/seller write the rest of his name as a signature of sorts.

Second, and along the same lines, but even more conspicuously: the format of the date in the document. The date — August 8, 1945 — is in the Christian (Gregorian) calendar, while both official and regular Saudi citizens at the time the document was composed used (and continue to use today) the Muslim (Hijri) calendar. Officials could use both calendars in government documents intended for Westerners (see the hujjah of Halwaaji), but there is no way in the world that a regular man from the tiny, poor fishing and pearling village of Saihat could have known the date of birth of a horse in the Christian calendar, let alone been able to convert it on his own from the Muslim calendar to the Christian one — this whether he bred the horse or not.

Even more, the word used for the month of August, Aab, is specifically the word the Shami and Iraqi (bascically the people of the Levant) use for this month. Some background here: There are at least three sets of names for the months of a year in the Arabic language. The first set is that of the Muslim names for months (Ramadan, Sha’ban, Rajab, Safar, Jumada, etc), which are used in the Muslim (hijri) calendar; the second set is the ‘modern Arabic’ names for months, and is an Arabization of the Western names (Yanayir for January, Fabrayir for February, Yuniu for June, Aghustus for August, etc); this set is typically used in Egypt when the Christian calendar needs to be used; the third is the Syriac calendar used by the Shami and Iraqis, which traces in direct line to the ancient Babylonian calendar (the names of months are the names of ancient Babylonian gods and religious feasts; specifically, the name Aab for August dates back to the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh). It’s a very different tradition than that of the Gulfi people of Saihat. Now, guess what, the date of birth of Walid El Seglawi in the document above is in the Syriac calendar…

The bottom line here is that the hujjah of Walid El Seglawi was written by someone from the Levant, most likely a Lebanese, Syrian or Palestinian Christian cleric employed with ARAMCO, while the name at the end, or rather the second half of it, was written by a different hand, likely that of Hasan son of Mansur the Saihati himself.

Third, the wording of the text iself. Note the use of the passive voice throughout: “let it be known”; “was sold”; “was bred”. This is very different from the usual format of hujaj, where the breeder or owner solemnly declares, swears and testifies about the authenticity of his horse “I swear that I bred this horse…”; “I testify that this horse is authentic”, etc. It’s as if the cleric who drafted the document wanted to put some distance between himself and the Saihati breeder/owner of Walid El Seglawi, even as if he was drafting a document in the latter’s name. The fact that the Saihati bred the horse and sold him to Nicholas Lederle Sr., is inferred, not explicitly mentioned. If one takes the text literally, it even looks as if the Saihati was not the breeder, but only the owner of the sire and dam. He may have bought the dam already in foal to the stallion, which would explain the use of the passive voice. He may have bred the horse, and the Shami or Iraqi scribe may have not known how to render that properly.

Fourth, the absence of religious, let alone Muslim, connotations. Allah’s name is never invoked (no “In the name of God” at the beginning, no “and God knows best” at the end) in the document, nor is the Prophet Muhammad cited. Whoever wrote this document was unfamiliar with how Muslim Arabs composed hujaj, and drafted it the way they would a regular administrative or commercial transaction. This unfortunately weakened the document, because the voice of the Saihati, his honor, his word, etc., are lost in the process.

What redeems the document and the horse is the explicit reference to the badiyah — the steppe or semi-desert, which is the dwelling place of the bedu or Bedouins — and also the reference to the tribe the sire and dam came from: Bani Khalid. This was once a powerful and important tribe, that established an emirate that ruled Eastern Arabia on and off for some hundred and fifty years, confronting both the Ottomans and the first Saudi State. The Abbas Pasha Manuscript is replete with mentions of the former ruling family of this emirate, the clan of Aal ‘Uray’ir, and their horses. They even had Saqlawis.

The Saihati may well have bred Walid El Seglawi, but he seemed to have known little about the horse’s origin, beyond the strain of the sire and dam and the general affiliation with the Bani Khalid tribe. No breeder of sire or dam is mentioned. This is not surprising, as Saihat in 1945 was a Shi’a Muslim community of fishermen and pearl divers, not Bedouins warriors or horse breeders. The fist name of the Saihati — Hasan — does actually suggest a Shi’a origin. A drought, poverty or his settlement in a township may have caused one Bani Khalid Bedouin to sell his mare and stallion of “deep rooted origin” (i.e., of noble descent) in the village of Saihat, and the Saihati would have acquired them. That part of Arabia was undergoing unbelievably rapid social and economic change at the time, with many people finding different forms of employment with or through the ARAMCO oil extraction venture. That change was beautifully narrated by novelist Abd al-Rahman Munif in his masterpiece, Cities of Salt. It’s a novel I heavily recommend.

Finally, on the horse himself. Based on the photos below, he seems to have been tiny and was clearly stunted as he was growing. Again this is not inconsistent with the high poverty conditions that may have caused the original Bani Khalid owner of his sire and dam to part with them. However, the dark skin around the muzzle and the eyes, the deep jowls, the tail set, the high and extending wither, all indicate good breeding.

When done reading this article, compare the hujjah with my translation of the hujjah of the Saud mare Halwaaji. This was was written by the master of the horses of King Saud in the Royal stables of Khafs Daghrah.

I am extremely excited by the Syriac calendar, and by the connection to Gilgamesh. I had no idea that the old Babylonian calendar persisted today – thank you for the lesson!

I use it everyday :))

I also really like how much you have been able to reconstruct from the two hands, each in a different calligraphy; it had never occurred to me that there would be distinctive styles of writing Arabic in different countries. I also hadn’t reflected on the passive voice and the effectively secular tone of the hujjah while reading it, but I think pretty much every hujjah I have read (admittedly not many) has had some religious invocation, so this is definitely anomalous.

Close textual analysis of handwriting and stylistics and grammar generally yields interesting results, and you have drawn so much information out of just a handful of sentences.

I am not a learned scholar in the world of the Arabian, I know some things perhaps, not a lot. One of the things I thought was well accepted is that the breed is not known for it’s height or great size. In contemplation one of the things that I believe contributes to their stature, temperament and overall tenacity is that they are a product of their environment. Not advocating for poor living conditions at all but this Arabian does not look out of place in his environment. Maybe it is only the “western” eye that views size as an issue? I can’t say, I live in the west and have no contact with those who live in the east. He looks like a horse I’d like to ride, find my eyes particularly drawn to that shoulder. When I used to visit with Lee Oellerich he would point out the mount he would choose in a life saving situation and it was not particularly tall, – great legs, strong back, well sprung ribs with “room for lunch,” . . . . I learned to value what he valued in conformation, all very practical.

Emma, I was just talking about this with some folks the other day. I grew up riding Lippitt Morgans, which weren’t an especially tall breed of horse but they more than made up for their apparent deficits in height by being very sturdy horses with good bone and a wide sprung of ribs; I saw many people who were 6ft+ riding these Little Big Horses without issue. I’ve had many a friend and acquaintance tell me they needed a taller horse and they wouldn’t go below xyz height because they were ‘too tall’ for xyz height. I think they generally failed to understand the way a good rib sprung can eat up longer legs. I have a friend who is considerably taller than I am who rides Icelandic Horses (who are frequently pony-sized), and she doesn’t have a problem riding them — similarly wide in the rides. I tend to categorize Arabians the same way in my head as far as horse types go.

indeed Moira :-). Little-big horses is an excellent description because to call them ponies doesn’t really fit, they may be a pony by measurement but my experience of them is anything but “little” – their ancestry is legendary and they are capable of big deeds, it’s in their genes. How diminishing it is to reduce them to the show ring where they get clipped, made up and paraded around. Ha, don’t get me wrong, I love watching my crew fly around their paddocks when the wind is whipping at their heels (or whatever may have inspired them to animate) – that’s exciting to watch for sure.

Moira and Emma: Its particularly refreshing to ,’hear,’ you speaking of taller folk riding so called small horses. Our present day standards of what is appropriate for long legged six footers to ride are rather warped by our show system. I suspect it is much more reality based for us to make use of what the endurance community has found to be really true- based on literally thousands of people in the saddle hours.. That the rider if she or he stays in balance with their horse can weigh up to 22% of the horses weight and still be very competitive with extremely light weight riders. Its worth noting that the old U.S. cavalry standard was that the horse could carry 25% of its weight in rider and tack without suffering. But the cavalry were very well trained riders who were held to a high standard by their farrier sargents , and they used the McClellan saddle a rig that’s very well designed to ensure the horses back stays cool and doesn’t develop saddle sores.

If you look back at historical photos of the u.s. cavalry you frequently see the riders legs down well below the horses belly so our obsession with size doesn’t appear to be based on real world paradigms.

best

Bruce Peek

The other day a friend of mine came to visit, and we pulled out my collection of saddles and had a nice day of trying them on my horses and talking about the way they did and didn’t fit. We ended up discussing trees and bar angles, and how baffled we were at the plethora of saddles on the market that are incredibly narrow. It’s so divorced from our experiences with Arabians and mustangs and Morgans. Who ARE these horses that are so narrow, so slab-sided, that such narrow saddles can fit atop? I won’t name the stallions, but I worked with a few top level Warmblood stallions a few years back who were really narrow in the chest and the ribs – hardly anything there – and it had me wondering. A lot (but not all) of Thoroughbreds seem to be built like this, too. I have a personal theory that as sport horses have grown to focus on height, they’ve sacrificed width…

I agree with your theory, 100%, Moira. I have observed the same in some Arabian horses at endurance events. Taller horses with narrower chests.

Hi Carrie, I have found myself contemplating the conformation of a “front” end of a horse. Lee used to speak about a “flat shoulder” and I am still working out what this is exactly. I have wondered if a horse has a well laid back shoulder with ample room for heart and lungs, and has excellent free range of movement . . . perhaps the chest being a little narrow is not as consequential? Idk. Just sharing thoughts. Have looked on the net to see if I can find information on this and there was precious little mentioned about this last I looked. I know this is a deviation from height. Probably have to study a skeleton or something. I did find something years ago on a fb group about it, dedicated to the conformation of Arabian horses. And lost it, and am also not on fb anymore but perhaps it’s out there somewhere. Will look again . . . wish me luck.

Width of chest is primarily a function of condition. A starved horse will be narrow. Once the horse is conditioned, a narrow chest can be broadened in balance by teaching the horse to march backwards, and to exercise in that way multiple times a week. I was taught that by a Quarter-horse friend. He said that was how they put chests on QH for halter showing. It certainly worked with my spindly Arab/Saddlebred filly.

FWIW, horses can also hold a lot of tension in their chests

I have observed this difference too between horses starved in the desert and then when they are better fed. It’s striking.

Thank you for another very educational article about the documentations. I very much appreciate and enjoy your writings.

You’re welcome. More coming.