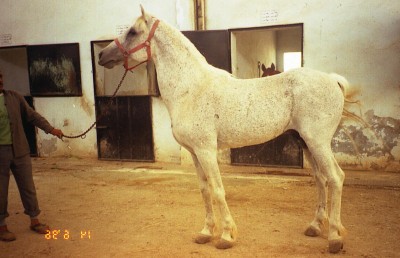

Remembering Mabruk, the desert-bred Kuhaylan al-Nawwaq stallion

This horse should have been mine, years ago. Actually, he was about to be mine, and he somehow slipped between my fingers by going to greener pastures.

I first encountered him on a hot summer afternoon in 1996, while on a visit to the Aleppo Equestrian Center, with friends Radwan Shabareq, Kamal Abdul-Khaliq, and my father, Salim al-Dahdah. We had come to see a famous Arabian mare, owned by a man of the leading clan of the Shammar, the Jarba clan, with the intention of buying her. She was a celebrated mare in the desert, and I have featured her several times on this blog.

The Aleppo Equestrian Center is located inside a gated compound; a paved road takes you from the main entrance to the stables and the administration offices uphill. Paddocks and jumping competition arenas are in the middle of the compound. As the four of us were walking up the paved road to the stables, the afternoon sunrays pounding on our heads, I was faced with this un-real image of a light grey Arabian stallion, tethered to the paddock fences, with a majestuous yet very gentle attitude, one that welcomes and inspires awe at the same time. I thought to myself: “I didn’t know they had Egyptian stallions over here, as the image was reminiscent of images of stallions like Hamdan, Sid Abouhom, or ‘Adl in old age. As we walked past him, I realized that he had noticed us, as he pointed his ears, yet his posture remained unchanged. Not even a look. “He is ignoring us”, I thought.

Once in the stables, they showed us the ‘Ubayyah mare, today registered under the name of Reem al-‘Oud; she still tops my list of the best asil desert-bred horses of all time. We took several photos, and I inquired about the stallion who was standing outside, and, while it’s considered rude to ask to be shown a horse your hosts may not have wanted to show you, I asked the staff to bring him in.

“You mean old Mabruk?” said one groom with a affectionate smile. “He has been at the Center for about twenty years, and is a local jumping champion, who’s won the Center’s Cup several times. He still participates in contests from time to time”. They brought the horse in, and I was shaking as I took the picture above (click on it to enlarge it), which in no way reflects the presence of the horse and the impression he makes on you. I noticed the groom was handling him with extra care, and pacing his walk on the horse’s walk, and while I assumed this was out of deference for an old pensioneer (the deep bonds between old grooms and old Arabian stallions should be the subject of a book of their own), I still asked the groom what was so special about Mabruk.

“Oh, it’s just that he’s blind, and has been so since he was four”, said the groom as if it was not even something worth mentioning. By now my father, who had overheard my conversation with the groom, had quit thinking about the mare, and started asking him questions about the horses’ origin, his breeder, strain, marbat, etc. This was always a sign that he was getting interested, and it was good news. I knew we had come for the mare, but now I wanted the stallion, too.

“He is Kuhaylan al-Nawwaq (alt. spelling, Nowak) and his breeder sold him to the Center as a young horse”. Who was his breeder? “Oh, he was one of the Bedu, one of the sons of Fanghash; there was a drought in the steppe and he had to sell some of his horses”. What!? Fanghash al-Nawwaq, the owner of the strain, from the al-Gasem clan of the Sba’ah? “Yes, that’s him”. By now, my father wanted the horse too, and I could not control my heartbeats anymore.

We asked if he was for sale. They said that we would have to talk to the Center’s director, who was absent, but that they believed he would just give the horse away to us. We asked if he was registered in the Syrian Arabian Horse Studbook. They said he wasn’t, that the Registration Committee came to inquire about him several yaers ago, but were told that the horse’s papers had been lost, so they left. There was nobody to testify on behalf of the horse, because he had been cut away from his original Bedouin environment, and had been at the Center for so long. There was also no way to contact his breeders, who may have been able to recognize him, because they had left the country long ago. This precious treasure simply fell between the cracks, and he was wasted. I could think of at least a dozen studs in Syria who could have improved their stock by using Mabruk.

Now we had to leave, and I made my father promise me to come back here and bring Mabruk back with us. He said: “What will you do with an old blind horse that is not even registered, and is without papers?” I answered that I would breed him to the ‘Ubayyah mare, who was not registered either (although she eventually was, eight years later). He smiled. When we came back to buy Mabruk (and the mare) several months later, we were told he had just died. It was just not fair. He should have mine. I am not over him yet.

Thank you Edouard so much for this story. What a telling story not only from a personal level but revealing the irony of asil Arabian horse history. No doubt all throughout time, there are special horses like Mabruk who must have slipped through the cracks. But such horses are teachers because they symbolize the true ideal of the breed from its original owners. Experiencing the loss of Mabruk is a great teaching moment. It reminds us to make sure that we learn to value what we DO still have and that we do not overlook something we cannot afford to loose.

First class horse in the way his body fits together. Do we have an Al-Khamsa horse that resembles him?

Thanks Edouard for sharing this story.

I found a record of Mabruk in the Syrian hujaj. He was the maternal grandsire of a Nawwaqiyah mare from Abd al-Jalil al-Naqashbandi (Not Aaliyah, not Hanadi, not Safiyyah, not Haidariyyah but the other one left). He is referred to as the Kuhaylan al-Nawwaq, horse of Rashid al-Nawwaq at the equestrian center in Aleppo. His sire is even given: the black Saqlawi Marzaqani of Shaykha al-Anud. This makes so much sense. So he has left progeny after all.

That is such good news. Every line represented helps the genetic spread. The Syrian war has been such bottleneck.