Speculation on Linden Tree (and Leopard)

I am cross-posting this here from another place that I had written this, and would love to pick everyone’s brains on their thoughts. Full disclosure: this was jumpstarted by reading Teymur’s posts here on DOTW and by reading and re-reading Michael Bowling’s three part series on Leopard and Linden Tree (…and perhaps by some personal spite re: the long-dead Randolph Huntington. I ended up not overly caring for his theories on breeding.)

~~~

^ Source: The Illustrated Stock Doctor by J. Russell Manning, published 1890, pg 66.

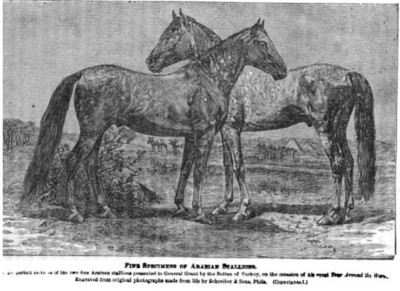

FINE SPECIMENS OF ARABIAN STALLIONS

The horse on the left, facing right, on the foreground, is likely LEOPARD. The horse on the right, facing left, on the background, is likely LINDEN TREE. Leopard was from the Fid’an tribe, the very same Jedaan that the Blunts once visited – according to Carl Raswan, at least. The issue of Linden Tree’s provenance is a little thornier.

General Grant was convinced of his purity by merit of the horse having been gifted to him. On the other hand, in his 1885 book “History in brief of “Leopard” and “Linden,” General Grant’s Arabian stallions, : presented to him by the sultan of Turkey in 1879. Also their sons “General Beale,” “Hegira,” and “Islam,” bred by Randolph Huntington. Also reference to the celebrated stallion “Henry Clay.” Randolph Huntington clearly felt that Linden Tree was a purebred, even going so far as to state that Linden Tree was the better of the two stallions.

He, of course, later changed his mind. In the March 17 1094 Volume 69 printing of The Country Gentleman, Huntington can be quoted as having written:

“It was through careful breeding I demonstrated that one of Gen. Grant’s two Arab horses was a pure Barb, and Hegira Is living today as limber, vigorous and active as any four-year-old colt, although he will be 22 years old this spring of 1904, and is just as sure in the stud.” (pg 254)

^ Caption: [Arabian horses presented to General Grant by the Sultan of Turkey]

Hegira, named above in the afore-listed 1885 publication, was “a coal-black with a faint star and white on all four feet. He was got by Linden from Nell Pixley by Henry Clay; was foaled July 9 1882, and stands fifteen and one-quarter hands high at three years old. Nell Pixley, his dam, was bred by Supervisor Pixley, of Monroe County, New York. She is fifteen and one-half hands high, strong.” (pg 27)

In another publication relating to the Americo-Arabs, The Pure Arabians and Americo-Arabs (Huntington Horses), published by Hartman Stock Farm (owned by Samuel Brubaker Hartman, medical quack extraordinaire of Peruna fame) of Ohio in 1908, it was said:

“Mr. Huntington concluded after much careful investigation as well as his extensive experience in breeding to these horses, that Linden Tree was a Barb Arabian pure and simple, and that Leopard was a pure Arabian horse of the Seglawi-Jedran strain from the desert of Arabia. I am confident he is correct in this conclusion.“

It would appear that in the nearly 19 years since he first published on the Grant Arabs and his column in The Country Gentleman, Huntington had changed his mind on the authenticity of the horse known as Linden Tree. This is somewhat ironic, given that he had earlier written to General Grant for information on these two horses (and the latter of whom you may recall knew virtually nothing of their origin), writing: “I became quite anxious to know all particulars relating to them, lest in future days some as yet unborn writer should tell his readers that General Grant’s horses were genuine imported Barbs, or maybe Andalusian horses, when any old man knowing to the contrary would be disputed into silence.” (pg 15)

Part of what informed Huntington’s opinion on what a Barb might look like was influenced by his examination of various Arabians and Barbs that came to the States. One example is Canadian breeder John B. Hall’s BLACK EMPEROR, who was apparently a gift to him from the Sultan of Morocco in 1875; Huntington may of seen this horse, but he most certainly saw the offspring, having had in his herd a granddaughter of Black Emperor, the mare PRINCESS OF MOROCCO to be mated with his Americo-Arab stallion Abdul Hamid II. Additionally, James S. W. Langerman, the Vice-Consul at Tangier, managed to bring 6 Barb horses to the United States for the St. Louis Exposition, a clear example if there ever was one. A photo of one of these Barbs may be viewed in here. Huntington was a prolific writer, and known for his lengthy and fiery debates with other equine enthusiasts on the differences, similarities, and merits of both the Barb and the Arabian, and he claims to have quite the extensive education on what constitutes both.

It may be that Huntington had suspicions that Linden Tree was a Barb, even from the beginning. Also in his 1885 book, he wrote extensively on the characteristics of Linden Tree that, to his way of thinking, showed the unassailable purity of the horse. He can also be quoted as having said, “I became quite anxious to know all of the particulars relating to them, lest in future days some as yet unborn writer should tell his readers that General Grant’s horses were genuine imported Barbs, or maybe Andalusian horses, when any old many knowing to the contrary would be disputed into silence.” (pg 15) The irony, in that, is that he himself became the man in future days to tell his readers that Linden Tree was a Barb.

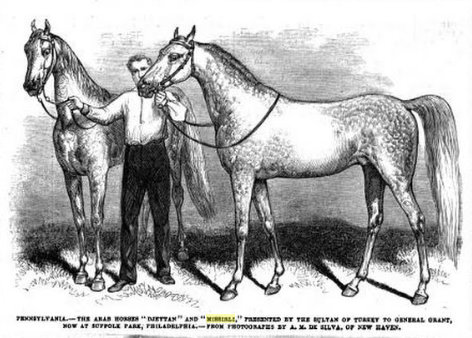

^ Caption: [The Arab horses “Djeytan” and “Missirli” presented by the Sultan of turkey to General Grant, Now at Suffolk Farm, Philadelphia. — From photographs by A. M. DE SILVA, of New Haven.] [x]

The peculiarity of how this came to be is that it seems that a good deal of Huntington’s theory on Linden Tree being a Barb was based on breeding, and that Leopard and Linden Tree produced such noticeably different types of offspring that they couldn’t possibly be of the same breed. To note:

- He believed in consanguinity as a breeding practice, that is, the mating of like animals to produce horses whose family traits are magnified. Known as linebreeding to some, Huntington took it to a rather extreme degree. He as also fond of using terms like “virgin mare,” if that tells you anything about his rather antiquated mode of thought. Therefore, if you breed like to like, you will get like.

- A direct quote from an article he wrote in 1894: “My friends Interested in horses expressed astonishment that I should mate a stallion with his dam. But in fact the polygamous animal kingdom reach the highest perfection through closest blood coitions. Nothing will prove purity of blood In domesticated animals as thoroughly as such a union. Crosses are mongrels, and all crosses tend to generate diseases and to shorten life, except crossing be continued ; cross-bred animals, under the restraint of man thrive through continuation of crossings.”

This alone is insufficient evidence, however. Just because Linden Tree didn’t fit in with his idea of what an Arabian should produce when mated to Arabian-descended horses (ie: the Clay Horses, and some of the English Arabians that he imported), doesn’t ipso facto mean that the horse is, in fact, not an Arabian. After all, while they might both have been genuine Arabians, the nature of the desert horse and the people who breed them is that there is an allowance for all kinds of variation of type. One of the noted scholars of the breed, Carl Raswan, is famous for pushing the strain theory, and the notion that you can judge a horse based on its conformational traits. It would not have boggled the mind to think that, perhaps, Linden Tree and Leopard came from slightly deviating desert genetics.

To this end, however, as is always the case with the Arabian horse, it was far more important to seek out the provenance of the horses. We know that General Grant received these horses from the Sultan of Istanbul – Abdul Hamid II – but even that isn’t sufficient. It would of course help to know the names of the horses before they became “Leopard” and “Linden Tree,” as names are important for Arabian horses.

To that effect, we must look to sources of the time.

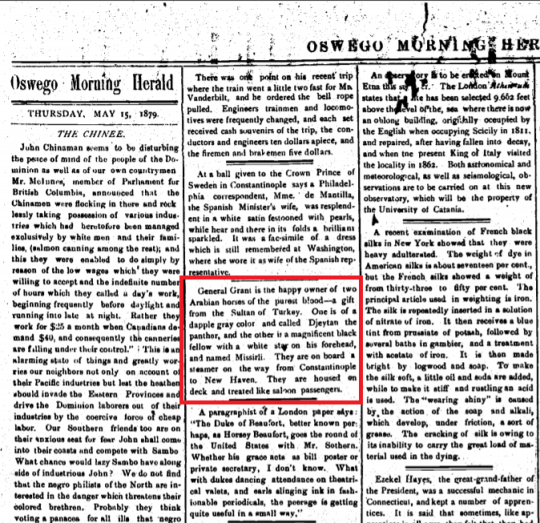

In the Oswego Morning Herald, Tuesday May 15th, 1879, it is stated:

“General Grant is the happy owned of two Arabian horses of the purest blood – a gift from the Sultan of Turkey. One is of a dapple gray color, and called Djeytan the Panther, and the other is a magnificent black fellow with a white star on his forehead and named Missirli. They are on board a steamer on the way from Constantinople to New Haven. They are housed on deck and treated like saloon passengers.”

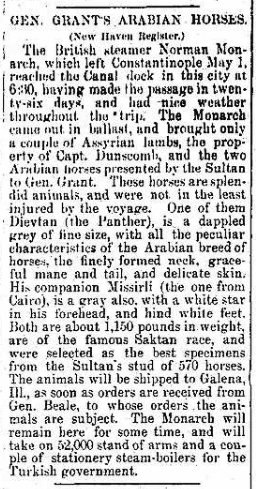

Then, in the Daily Journal, Saturday June 7th 1879, it is later stated:

“GEN. GRANT’S ARABIAN HORSES (New Haven Register.) The British steamer Norman Monarch, which left Constantinople May 1, reached the Canal dock in this city at 6:30, having made the passage in twenty-six days, and had nice weather throughout the trip. The Monarch came out in ballast, and brought only a couple of Assyrian lambs, the property of Capt. Dunscomb, and the two Arabian horses presented by the Sultan to Gen. Grant. These horses are splendid animals and not in the least injured by the voyage. One of the Djeytan (the Panther) is a dappled gray of fine size, with all the peculiar characteristics of the Arabian breed of horse, the finely former neck, graceful mane and tail, and delicate skin. His companion Missirli (the one from Cairo), is a gray also, with a white star in his forehead, and hind white feet. Both are about 1,150 pounds in weight, are of the famous Saktan race, and were selected as the best specimens from the Sultan’s stud of 570 horses. The animals will be shipped to Galena, Ill., as soon as orders are received from Gen. Beale, to whose orders the animals are subject. The Monarch will remain here for some time, and will take on 52,000 stands of arms and a couple of stationary steam-boilers for the Turkish government.”

(Bolding added by me for emphasis.)

This would of course refer to their arrival to the States in Philadelphia.

Djeytan, of course, is Leopard – a curiosity of naming given that his Arabic name was panther, and an interesting contrast to Carl Raswan, who in the Raswan Index entry #5548 stated that Leopard’s original name was in fact Nimr and that Djeytan was but a confusion of Jedaan. Missirli, on the other hand, fits the description given by Randolph Huntington for Linden Tree, though he makes a point to correct that the horse is actually a very dark grey horse in the beginning stages of his greying process:

1, pg 11: “Linden Tree (or Linden, for short) was now led out. This horse has been called a “jet black” by some papers, which was a mistake never corrected by such journals. At that time, the spring of 1880…?

2, pg 12: “…Linden was a beautiful, smooth, blue-gray, which this summer of 1885 have chanted to a white-gray.”

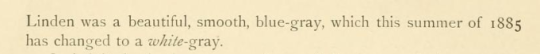

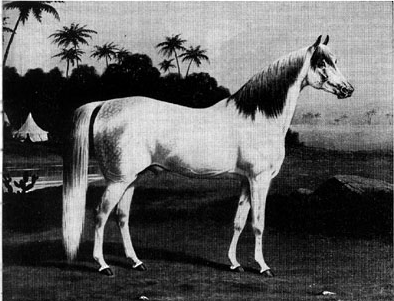

Likewise, the drawing by equestrian artist Herbert Kittredge in 1880 of Linden Tree shows that he very obviously has has two white socks in the hind end:

And finally, in respect to the colors of the horses and in confirmation of their identities, they are described in an accounting of Grant’s travels abroad as:

“One is a dappled gray of fair size, and having all the traits characteristic of the Arabian blood — small, -well-set, restless ears, wide, pink nostrils, and large, soft eyes, waving mane, and long tail reaching almost to the ground, and a skin of such delicacy that the stroke of a lady’s whip is sufficient to draw blood. The other stallion has all these points. He is an iron gray, with a white star on his forehead and white hind feet. When the long forelock falls over his forehead the large black eyes have all the expression of a Bedouin woman’s. Their gait is perfect, be it either the rapid walk, the long, swinging trot or the tireless, stretching gallop, while a rein of one thread of silk is enough to guide their delicate mouth. Let one of these Arabs in the mad rush of a charge or a flight lose his rider, and that instant the docile steed will stop as though turned to stone. These horses are of the famous Saktan race, the purest Arabian blood, only found in and near Bagdad. The dapple gray is appropriately named Djeytan (the Panther) and the iron gray Missirli (The One from Cairo), which cognomen he derives from having been bought at Cairo, though foaled at Bagdad.”

Missirli is given as as meaning “the ‘One from Cairo’” in The Life and Travels of Ulysses S. Grant, written by Joel Tyler Headley and published in 1879. This meaning, and in theory therefore the provenance of the horse, is supported by the fact that the etymology for the word Missirli does, in fact, mean Egypt. Which could very well contradict the mainstay narrative that Linden Tree was a Barb born in the stables of Abdul Hamid II.

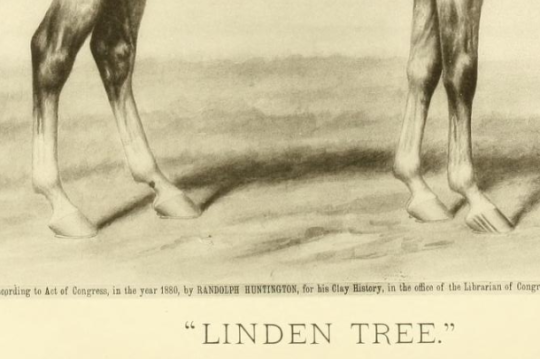

There are a number of stories on how General Grant specifically came to acquire these horses, but these accounts are somewhat contradictory and most*** seem to be of little consequence beyond the fact that Grant was reluctant to take them. For an article in the 1896 40th Volune of Harper’s Weekly on the PURE ARAB, Spencer Borden wrote:

Ironically, Borden for all sakes and appearances inherited Huntington’s program and his vision of the Americo-Arab, but it seems that he also held Linden Tree in high regard, and that once again we can confirm that Linden Tree – or Missirli – came from Egypt and that he was unconvinced that the stallion was not, in fact, a purebred Arabian after all.

So, if both Linden Tree-Missirli and Leopard-Djeytan were foaled in Egypt, or at least brought to the Ottoman Sultan from Egypt, it becomes a matter of tracking who bred them, and if their strains exist.

So here’s what we know from these accounts:

- Linden Tree = Missirli

- Leopard = Djeytan

- Huntington believed Leopard’s strain to be Seglawi-Jedran

- Contemporary sources list them as both having been from Egypt, or perhaps bought from Egypt

- Contemporary sources also list them as being of the “Saktan race…only found in and near Bagdad,” located in modern-day Iraq

Item no. 3 of the above list is of paramount interest, as the strain name attached to an asil Arabian is tantamount to his birth certificate. To use a metaphor Edouard al-Dahdah once used, it would be like presenting your passport in a foreign country you have traveled to as a means of identification. So where, pray tell, did Huntington discover this strain name, and what evidence did he have for this?

A look at the The American Stud Book Vol. 6 published in 1894 shows that at least by 1893, when the studbook was being compiled, Huntington had discovered this information – listing both Leopard as a Seglawi-Jedran and Linden Tree as “Gen. Grant’s Barb (called Arab) Linden Tree.” Likewise, Huntington published an article in The Cultivator & Country Gentleman, Volume 59 (June 1st, 1894), page 458, where Huntington himself called Linden Tree an Arab-Barb and states: “I bred Naomi to Anazeh as a test of the blood of Leopard, fr knew positively that Leopard was a pure Seglawi-Jedran Arab, or I would not have bred Naomi to him. The horse by him, Anazeh, is perfection of perfectness, mental and physical. A union of the Maneghi-Hedrudj with the Seglawi-Jedran, is considered by the Anazeh tribes to give always the best horses, combining beauty with quality, and with increased size to the Seglawi blood. A union of the blood of the mother and son, would give me condensed brood values in the offspring, for stock or brood purposes.”

This does, in theory, support the idea that he might have identified what he believed to be the provenances of both Linden Tree and Leopard before this mating. The foal in question, NEDJ, was foaled in 1894, and who was the third purebred Arabian to be born on American soil – the second, Rahman, predated him (b. May 23rd), and was out of Rakusheh by Jamrood — you can find the announcement on page 25 of the same publication. The first was Nejd’s sire, ANAZEH (Leopard x Naomi), born in 1890. In theory… Huntington may have known Leopard’s strain name before then, as Naomi was the jewel of his crown in terms of pure Arabian breeding, but it’s equally as possible that he had planned to breed her and Leopard as part of his Americo-Arab project without knowing the provenance of the stallion in question.

That said – if we jump forward to the Jockey Club’s 1884 publication of The American Stud Book: Volume 4, Linden Tree and Leopard are listed as thus:

1, [LEOPARD, gr. h., foaled 1872; bred by the Sultan of Turkey, and by him presented to Gen. U. S. Grant; owned by J. B. Houston, New York, 1883.]

2, [LINDEN TREE, gr. h., foaled 1875; bred by the Sultan of Turkey, and by him presented to Gen. U. S. Grant; owned by U. S. Grant, Jr., New York]

^ Ulysses S. Grant, Jr.

As an interesting sidenote, four years later, in 1888, Grant Jr. sold Linden Tree to Gen. S. W. Colby, of Beatrice, Nebraska. This was reported in the National Stockman and Farmer, Volume 12 (May 31 1886), and it marks Linden Tree’s beginning as one of the foundation sires of the Colorado Ranger breed.

So then we come closer: and it is by Ben Hur in his 1947 May/June article of Western Horseman (republished on the CMK website) that our primary piece of of evidence re: Mr. Huntington’s belief that Linden Tree was a Barb:

“Nevertheless, Mr. Huntington was so enthusiastic about the General Grant Arabians and their pictures that he wrote a book entitled General Grant’s Arabian Horses, published in 1885, in which he expounded at length his theories of breeding and pedigrees of his American made horses. One of these rare books is in possession of the writer, inscribed “Presented by the Author, Randolph Huntington.” Under the picture of Leopard in Mr. Huntington’s handwriting is written: “Proved a Seglawi-Jedran.” Under the picture of Linden Tree is written “Proved a pure Barb.”

Obviously, this proves… nothing. Just underscores once again that Huntington did indeed believe that these final versions identities of the horses were the correct ones.

It does not, however, answer the question of whereupon the identity of Leopard as a Saglawi-Jedran come into Huntington’s knowledge-base, nor does it give us any idea how Huntington came to confirm that Linden Tree was indeed a Barb.

To the latter point, it is necessary to revisit the story of the acquisition of Linden Tree: in that Randolph Huntington and Major C. A. Benton allegedly investigated his origins, and Benton, according to Ben Hur (also in his 1947 May/June article of Western Horseman), made inquiries that ultimately led to the discovery of Linden Tree’s provenance:

“How Linden Tree could have been a Barb and yet presented by the Sultan to General Grant as a pure Arabian was related to us prior to 1930 by the late Major C. A. Benton, Civil War veteran, who devoted his life to horses related to military action. Major Benton was personally familiar with each and every Arabian in this country in the formative period of the stud book and club. A few years after the Grant importation he was sent on a military mission which took him to Constantinople, among other foreign ports. The Major related to us on several occasions how he sought out the keeper of the Sultan’s stables and questioned him about the Grant stallions. It developed that on the day before the horses were to be loaded on shipboard the stallion selected by the Sultan as a gift to General Grant had sprained a leg and was lame. Rather than report the accident to the Sultan and possibly lose his position, he selected another horse in the stable as near like him as possible. The horse was a Barb. We have, then, from two early authorities that Linden Tree was a Barb. It is significant that in all the early editions of the stud book when family names were given to all registered, the word “Unknown” is given after the word “Family” in Linden Tree’s registration.“

To parse — According to Benton, Linden Tree was a stand-in for the original Missirli, and Grant sent him to American soil none the wiser. This is, of course, a secondary source material detailing an account of an inquiry made by somebody after the fact of the importation. The fact in the matter is that until we see the primary sources

^ Another rendering of Linden Tree.

Homer Davenport in his 1909 book “My Quest for the Arab Horse” has this to say on the acquisition of the horses:

“At the time we were in Constantinople it was not entirely easy for foreigners to witness the ceremony, but permission to visit the Imperial stud was easily obtained through Mr. Gargiulo. Mr. Gargiulo was with General Grant on the latter’s visit to the Royal stables, when the Sultan offered him a stallion, which the General at that time refused. Later, when in France he saw what use France had made of the Arab blood, he wrote saying he would take the one offered. Mr. Gargiulo told the Sultan how lonely a trip to America would be for one stallion and that two would travel better together. Accordingly the Sultan gave two. His Majesty picked out a gray and a black, and as they were being prepared for the trip, Mr. Gargiulo tried them, and found the black was not a good saddle horse. He had to think of some scheme by which an exchange could be made, but he knew he would have to have a good reason. Final ly, as he went to the Master of Ceremonies, to thank him for the stallions for the General, he said: “But ”

“But, what?” said the Master of Ceremonies, with some heat— “you first ask for one, then for two, and when all this is granted, you say, “But— But what?”

“But — I have found from careful inspection of history,” answered Gargiulo, “that no American ruler ever rode a black horse. Will not His Majesty send a horse of some other color for the black one?”

The Master of Ceremonies made note, and said His Majesty should be told.

The next day another horse had been chosen, a darker gray than the first one, which must have been “Linden-tree,” as he was the darker of the two, and a better horse. Mr. Gargiulo said that as far as breed was concerned, no one knew their blood, they were just presents to the Sultan, and presents from the Sultan to General Grant, of no known blood, and were sup posed to be pure Arabs. I told this distinguished old gentleman that “Linden-tree” was much written of in America as a barb, when he laughed heartily, adding: “No barbs were ever in the Sultan’s stable, as he does not like the people, much less the horses.“

TL;DR – Linden Tree was not part of some secret switerchoo, but indeed a formal switch had been made, not because the horse was lame, but because it was not a good saddle horse. According to this account, General Grant may not even have been around to see the second horse be picked out, which is a bit contradictory, but not necessarily incorrect, as we do not know. What is perhaps most telling here is the final statement of the quote – which suggested that indeed there was a high likelihood of Linden Tree being, in fact, an Arabian.

Another important detail in this miasma of confusion is a single sentence written after this excerpt from Davenport’s book, on page 21: “The superintendent of the stables did not know the breeding of the horses, but when I asked about a beautiful gray stallion, he said he was of Bagdad breed.” Now, obviously this doesn’t confirm or disprove that either Leopard or Linden Tree were from Baghdad, but it does bear saying that it establishes a multiple-source reference to there being Arabians from Baghdad in the stables of Abdul Hamid, the Sultan of Istanbul.

A third piece of evidence, reported again by Davenport, actually predates his book publication by two years; he wrote, in the 1907 publication of Journal, Volume 40 published by Military Service Institution of the United States, the following of Linden Tree and Leopard:

“There was no mention of him being the pride of the Sultan, and neither horse was of any known breed whatever. They were simply presents from the Sultan’s stables; and, while examining thirty odd this last summer in the Sultan’s stables, we found, to our astonishment, that they knew of no breeding connected with them…”

Hold onto this quote as we delve further.

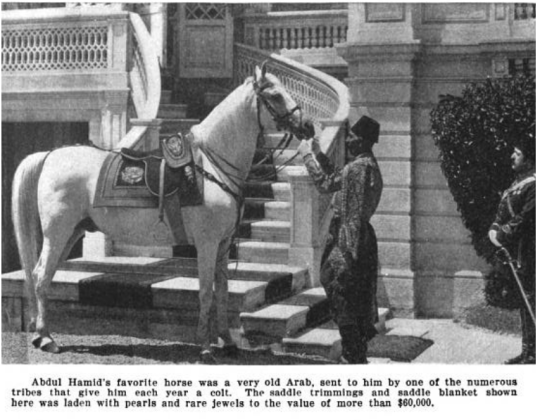

A final piece of important information from Davenport’s book is a picture and caption, as follows:

Caption: [Abdul Hamid’s favorite horse was a very old Arab, sent to him by one of the numerous tribes that give him each year a colt. The saddle trimmings and saddle blanket shown here was laden with pearls and rare jewels to the value of more than $60,000.’]

Davenport reports that the Sultan is sent a colt (read: foal) each year – the inference here being as a form of tithe or something similar. Thus, it is reasonable that the reason nobody knew of the origin of either Leopard or Linden Tree while at the stable was because they were horses sent to the Sultan for this very purpose. This is confirmed in Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Volume 37, published 1881, from the notes of the Ritter von Vincenti (likely this man), page 145:

“Sometimes the Arabian kings send, for political reasons, some horses as a present to the courts of Stamboul, Teheran, and Cairo ; as, for instance, Feissul the ‘ fat ‘ did at the beginning of the reign of the late Sultan Abdul Aziz ; otherwise the horse-dealers in the Syrian desert scarcely ever cast their eye on ‘ Nedschedi.’”

Which. Not terribly helpful. But while it does not outright prove that Linden Tree was in fact an Arabian, it also does not outright disprove that he was an Arabian.

To pursue this line of thought, if the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire frequently received horses from Baghdad, and if Linden Tree and Leopard were originally said to be from or from near the city of Baghdad, it bears further inspection. The other half of the identification was that they were “of the saktan race” – which could either have meant a people, or a place.

For the people – there exists a Banu Saktan tribe, however, most references place them at ~800 A.D., about a thousand years before the time of Linden Tree and Leopard. They are sometimes references as being a Berber tribe, again circling back to the Barb horses.

For the place, there exists a Sakt?n – in Iraq, no less, alternatively spelled Sektan. This is not overly close to Baghdad, but it’s closer to Baghdad than it is to Istanbul/Constinople.

But then again, Sektan might have been made up, or an embellishment told by those reporting the acquisition of the horses. Of course people would want to make it seem like General Grant was being eminently respected, and that this gift (really…. bribe…) was a mark of the highest honor! Who can say for sure – they’re all dead by this point.

Thus, the circumstances surrounding his origin as told by the early American breeders and friends of these Arabians can not, with surety, give us a good answer. And in the end, for those like Randolph Huntington, Spencer Borden, C. A. Benton, and Homer Davenport: Quod volim credimus libenter. “We always believe what we want to believe.”

There does exist another possibility, one unconsidered by the contemporaries and early successors of Linden Tree and Leopard’s time from a completely different angle: that the ancestor came from Polish stock, as there was a considerable interplay of horse exchange during the Westernization of the Ottoman Empire.

On this website, an alternative account of Linden Tree’s ancestry is offered, counter to the narrative that he was a Barb or a desertbred Arabian–

– *LINDEN TREE/Ihlamur A?ac?, Grey Stallion foaled in Abdul Aziz’s Ka?ithane – stables in Istanbul, from Inak;1857, Grey Stallion, b. Biala Cerkiew, imp. from Poland. His Dam “Doru Hamde”(Bay Hamda), was a Hamdaniye Simriye by a Maneki Sübeyhi.

These came from the Bedouins and also from the stud Bialecerkiew from Poland.

Linden Tree was born in 1874, specifically bred by Sultan Abdulaziz I. and not of Abdülhamid II.

In 1864 the Sultan Abdulaziz I, founded a new farm, building with Arabian horses and sent a commission to purchase in Bialocerkiew, the stud of Count Branicki in Poland, whose breeding have a very good reputation.

The Commission purchased 92 horses, including some descendants of the 1855 stallion Indjanin imported from England

This seems to come out of left park from nowhere, but the information is repeated by Teymur on this DOTW blog here and here and here. All of these posts talk about the breeding of Arabians in North Africa and in Turkey

Some things to break this down.

1. The name Ilhamur, placed after Linden Tree. Ilhamur is actually Turkish for Linden Tree, while Missirli denotes Egyptian heritage.

2. Abdülaziz, listed as the owner of the stables in which he was foaled. Abdülaziz was the 32nd Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and his reign spanned 1861 to 1876. If Linden Tree was born in 1874, that would absolutely fit the time line of him being a young – but still mature at 5 years of age – stallion by the time Grant visited and later was gifted him in 1879.

^ Sultan Abdülaziz I of the Ottoman Empire

3. Ka?ithane – stables in Istanbul. This is without a doubt the Ka??thane, a place that 17th century traveller Evliya Çelebi describes as:

“When the horses of the Sultan are turned into the fields in the spring for green food, the master of the horse dwells in this kiosk, where he gives a feast to the Sultan and presents him with two Arabian blood-horses, for which he receives a sable pelisse, and ten of his boys are taken into the Imperial harem as pages. It is a beautiful meadow, where the Arabian horses called küheylan, jilfidan, tureyfi, ma’nek, musafaha, mahmudi and seylavi are fed on the finest grass, trefoil and oats. . . . So famous are these meadows of Ka ithane, that, if the leanest horse feed in them for ten days, he will resemble in size and fatness one of the large elephants of Shah Mahmud (the prince of Gaznevis). The walk of the resort-lodge of Ka ithane is celebrated all over Turkey, Persia and Arabia. Turkish poets have praised its beauties in particular poems, called erengiz.”

A view of the stables kept in the time of Abdul Hamid II can be found here; note that you can see a copy of the photo posted above from Davenport’s book – the grey favorite of the Sultan, whose name is Asil.

4. Inak as a sire. On ABP there is a horse named Inak, foaled 1857 as given in this account of Linden Tree’s ancestor, also listed as having been bought by Ottoman Sultan Abdulaziz in 1864. His sire was Indjanin, a horse that is also specifically listed in this accounting. His original name was Nizam, who arrived in Poland via England via India where he was renamed Slawuta Indjanin. It is unclear if he is a desertbred Arabian.

5. Biala Cerkiew, is [x] also perhaps more recognizably translated as Biala Tzervka, a place that was visited by Wilfrid S. Blunt as told by his My Diaries: 1888-1900.-pt.2. 1900-1914. This is, of course, the site of the Branicki Stud. Blunt was obviously unimpressed with their bloodstock, but nevertheless, it tallies up.

6. References to the Sultan Abdülaziz purchasing Polish Arabians can be found online in several places, though their veracity is not unimpeachable; [1] [2] [3]

MUCH of the above information can apparently be found in Andrew Steen’s book “The Man Who Bred Skowronek.” (Note: I have not confirmed that this is all found in Steen’s book, but I do have the book on the way and plan to double-check this anon. If anyone else has this book, feel free to follow behind.)

IF this information is to be trusted (and we really need to see the primary sources), then the dam of Linden Tree was in fact a ““Doru Hamde”(Bay Hamda), was a Hamdaniye Simriye by a Maneki Sübeyhi.“ WHOM– in all feasibility, could have come from Baghdad, to bring the theory of his provenance as told by Westerners back into the fold.

To circle back to a far earlier question and item of interest, is the strain of Seglawi-Jedran for Leopard. As earlier mentioned, the only evidence we have available as to Huntington knowing the strain of Leopard is through secondary sources. We know that he believed this to be true, but what we don’t know is why he believed this to be true, and of what specific information he had at his disposal he had to inform this belief beyond what has already been stated.

More curious yet is his assignation as a Sawlawi Jidran bred by Jad’aan Ibn Mhayd of the Fid’an tribe. To quote the Al Khamsa page for Leopard: “According to Raswan Index entry #5548, the breeder of *Leopard (originally called Nimr, or leopard in Arabic) was Jad’aan (“Djeytan”) Ibn Mhayd of the Fid’an tribe, who had presented him to the Ottoman governor of Syria, who in turn presented him to Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid II. This entry describes *Leopard as a Saqlawi Jidran by a Kuhaylan Ras al-Fidawi. [See under Breeder, p15]“ This is, of course, suspect. There exists an understated knowledge in current contemporary circles that Raswan is not always a reliable source – despite having been so influential, he got an awful lot of things wrong, and it’s entirely possible that this is yet another case of ‘Raswan strikes again!’

This is certainly a fascinating line of inquiry, and it would be remarkable if we actually did in fact have a stronger idea of where Linden Tree came from than we do of Leopard, the latter of whom was formally accepted into the Al Khamsa database as a sire.

Sooo, completely coincidentally, I noticed this in the GSB Vol. 17 today:

“Kouch (Quoch), a Grey Horse, foaled about 1860, a Saklawi Djidrane of the desert between the towns of Bagdad and Mossoul. Presented by the Sultan of Turkey to H.R.H. The Prince of Wales, September 9th, 1867.”

Which I think is interesting re the possibility that Leopard and Linden Tree came from Baghdad, as it shows that Abdulaziz I received horses from the area.

Here’s something I just learned. Kouch has modern Arabian descendants through his 1884 son Gomussa out of *Naomi. Gomussa was exported to Chile, and Gomussa has descent through his Chilean-bred get Shema, Raschid, and Ramdy II, all out of Weil-bred mares. See for example this pedigree:

https://www.allbreedpedigree.com/oraya3

The photo of “the Sultan’s favorite horse, Assil” was identified in the Sultan Abdul Hamid’s photo albums as a Trakehner. The label under the photo is “Assil. Cheval blanc _ (Trakene)”

The caption used in Davenport’s Quest (2017) is “Although this horse, a favorite mount of the Sultan, is named ‘Assil,’ he is still clearly labeled as a Trakehner. The Sultan had many stud farms, and kept many breeds of horses. The Arabs appear to have been kept separately and so labeled.”

I was going to mention that too, Jeanne. There’s another photo of Assil taken at the same time, marked “Assil. Cheval allemand _(Trakene)” http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b46537/?co=ahii

Maybe the photograph was used by Davenport more to show the Sultan’s bejeweled tack?

I had seen that while digging up photos of this horse (there are some very nice ones to be found, including this colored postcard!), as well, but had also debated on whether it was relevant to add. While the original caption does say that the horse is an old Arab, the salient point in text was the second half of that sentence. BUT- I suppose that could also serve to discredit Davenport’s claim, though it may also be said that the claim of tithe-type horses being sent to the stables was correct while his identification of Asil/Assil as an Arab was incorrect. In any case, that information is here now 🙂

I never thought to ask, but now it’s come up: where does Kouch fall on asil status? He’s not in the Al Khamsa database, but that just means that he doesn’t survive in asil breeding today. Was there ever a decision on him from an academic standpoint?

Missirli indeed means “from Egypt” in Ottoman Turkish.

Also, I would not give a lot of credence to the information that the strain of Leopard was Saqlawi Jadran.

That was the most sought Arabian after strain, also one of the rarest, and many Bedouins and townsfolk merchants had no qualms telling a Sultan’s intermediaries and agents that a particular horse was from the strain he wanted.

Also, I did not find any evidence that Djeytan means “leopard” in Ottoman Turkish (which I don’t speak). Only that it means “devil”, “satan” or “demon”, cf. Arabic ‘sheytan’, Satan.

There’s a real lack of any sort of metaphorical (or even literal) paper trail for Leopard’s supposed strain. It is interesting, if not particularly illuminating, that Raswan seemed to conflate ‘Djeytan’ with ‘Jed’aan’ without providing any external sources for that claim. How the heck did he find the certifications for Leopard? (I think… he didn’t…)

And I can definitely see how Djeytan and Sheytan could be cognates. Which begs the question of where ‘Leopard’ came from, or if it was just made up by the Grant entourage.

That’s always another possibility, that everything about these horse’s identifying information was made up, from them being from Baghdad or anywhere near there (“pure Sektan race”), to them being named Missirli and Djeytan, and so on. General Grant and the officials writing back home would of course want to build up the success of their trip and the honor paid due to the United States, and it’s not outside the realm of imagination to posit that perhaps they made false claims to the horses’ origin. Grant was never an Arabian horse person, and it’s doubtful that any of the officials that went with him would have been particularly invested in them, either.

My thought is that there is too much confusing and conflicting information, none of it from primary sources, ever to sort it out. Maybe there is something more concrete in Ottoman archives.

RJ,

Right? I was hoping I could organize some of it a little more, because when I first started looking into it, I was VERY confused as to what all was going on with these two. I think I read somewhere that Joe Achcar had some of the Turkish studbooks in his possession, but I might be misremembering that. I suppose someone has already contacted people in Turkey to inquire about these archives – has anything come of that?

I have a copy of volume I of the Turkish stud book, but it was issued in 1995, and the earliest foundation horses listed were foaled between 1910 and 1920. Unless you mean some other Turkish stud books?

I don’t think anyone from here has successfully tapped the Ottoman archives.

The foundation horses in the Turkish stud book that I have were from the same era as Baba Kurus, for example (more on him here: http://daughterofthewind.org/krush-halba-a-k-a-baba-kurus-1921-asil-kuhaylan-krush-stallion/)

Oh, what a lovely horse!

And right. I suppose many of the Turkish national books really start after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. It seems much of the Ottoman archives is currently in the Kagithane, in any case, and they do have a website for their archives: https://www.devletarsivleri.gov.tr

Mmhh on Djeytan….i have seen some strange spellings for the Jutneh strain in the French studbooks which Jenny Lees sorted out for me. Could Djeytan be also the same?

Maybe.. Jutne = Ju’aythni, the strain of Yasser’s beautiful mare Bushra.. but Ceytan/Djeytan/Sheytan = devil was a common name for stallions back then..

Amelie – I confess, I haven’t heard of the Jutneh strain before. Could you provide some information for me?

Not a very common strain as far as i can tell from it being rare among the listed strains of imports. Edouard or Jenny might be the ones to ask about it with their encyclopedic knowledge. Possibly could match the Bagdadi area?

Also it is very likely a Bagdadi horse would have been sent to the Ottoman sultan. I have several references of this happening in the French records. Bagdadi horses were prised and often sent as gifts from the Pasha of Bagdad to various other important people to Constantinople or Aleppo and so on.

That’s right Amelie, and in Ottoman horse parlance, Baghdadi is a shorthand reference to a Shammar horse. From the viewpoint of the imperial center in Istanbul, as you correctly suggest, gif thorses came from the capitals of their provinces/vilayets. Hence a gift horses from Baghdad went through to the vali of Bagdad, whose vilayet covers the area where the Shammar (mainly those of Farhan Pasha al-Jarba at that time) nomadized. It is not a reference to the horse coming from the city of Bagdad itself.

J’aithiniyah. Is that the strain you are looking for? It exists in the Tahawi asil horses in Egypt.

Thank you for correct spelling Jeanne ^^

The “male” version of this name could sound like “Djeytan” to the Western ear maybe…

Oh, now I’m on the same page.

That’s actually a very interesting suggestion. The masculine form would have been something like J’aithin, which I could definitely see a Westerner interpreting as Djeytan. Some of the variations in strain names can get quite ridiculous (Sakla Wooyeh, Manaake Hedgrogi, and Liklany Gidran are some personal favorites of mine.)

What is more interesting still is carrying further the speculation of this name being a misapplied strain name.

From the Tahwahi horses, we know that Kuehila Jeaithiniya (or Kuehila of Ibn Jeaithin) comes from Iraq. To quote: “The line traces to the famous “Al-Mawali” tribe in Syria (from whom it was acquired by us in the early 20th century) then to the “Al-Amaraat” clan of “Anazah” tribe in Iraq from the stud of the notable grand sheikh of Al-Amaraat “Mahrooth Ibn Hazzal” who inherited it from his great grand father “Jeaithin Al Hazzal” after him the line was named as Kuheila Jeaithiniya. The line is extremely rare.” [x]

Hazzal appears to have many variations – Hadhdhal, Haddal, Heddal. This probably isn’t news to most of you, but it bears repeating that Ibn Hadhdhal is mentioned in numerous sources across the board – the Blunts bought a filly, Babylonia, from them. Rzewuski mentions them in the context of hostilities (possibly his enemy, or the enemy of a tribe he was allies/friends with). There’s even a connection between ‘Ibn Haddal’ and the Arabians brought over from India – the ibn Haddal Anazeh supplied horses to India via Abdul Rahman Minni, and horses such as Rataplan came to India that way. [x]

Lady Anne Blunt was not a fan of these horses, having written in “Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates” some rather disparaging remarks on the Ibn Haddal and their ‘tricks of the trade.’ She clearly felt that most of the horses bred by the Ibn Haddal were not purebred Arabians, and the few that were came instead from other tribes. Nevertheless, Roger D. Upton had a different opinion, believing the Ibn Haddal horses to be some of the finest specimens of Arabian horses.

The lovely Al Khamsa III picture of “Tribal Boundaries c1875-c1920s” shows that the Amarat (in connection with the Ibn Hahdhal/Haddal) tribal lands to extend all around what is Iraq, with the city of Baghdad overlapping within their territory. This does align roughly with a ‘close up’ view of the territory published by Carl Raswan, which, while not unimpeachable, can certainly be fact-checked. Either way, the Ibn Haddal associated with the J’aithin/-niyah strain was certainly located near Baghdad circa at least 1875, which is roughly around the time that Linden Tree and Leopard were born.

I know little enough about the history of the Near East (which I am scrambling to rectify), but there are references to the idea that in the early 1800s Ibn Haddal was present at the Sa’udi court in Diriyah, which is very interesting as it carries the implication that, for whatever reason, in the 1870s the Ibn Hadhdhal family had switched sides, as they evidently had accepted the Ottoman Empire’s rule. Kate was able to dig out a JSTOR article that mentions the sheikh of this clan – “In I872, for example, the Turkish governor summoned Abdul Rahman al-Hadhdhal of ‘Anayza to Baghdad and offered him tapu rights and the governorship of al-Muhsiniya district in return for persuading his tribesmen to settle down.” Per a wikipedia article (and hence my limited understanding of this at this time) the tapu rights, or tabu rights, were the permanent land lease rights of state-owned lands to non-royal families. What motivated this change, I really cannot say (perhaps older, more versed members of this community can help me understand the situation a little better 🙂 ) but it does seem that it might have something to do with Muhammed Ali’s reconquest of Arabia, or perhaps with the Rashidi clan being in power instead of the Sa’udis. Regardless, it would seem that the tribal allegiances would have shifted with the sands they lived upon, a sort of trading one empire for another to retain their tribal lands.

It therefore does not defy the imagination to speculate that, after taking in with the Ottoman empire, horses from the Ibn Haddal were presented to the governor of Baghdad, and ultimately sent to the stables of the Sultan. I have to wonder what kind of government records still exist of these transactions (if they do exist, presumptive upon the idea that these transactions did happen) and where they might be.

The link of the Ju’aythni strain to Ju’aythin ibn Haddal is Yasser and I speculating. We have no proof it until now. Note that the strain was common in present-day Iraq and rare in present-day Syria as Ali Barazi noted in his book. It was also well represented in early Turkish imports from Iraq, as you can tell from the table of Turkish Arabian foundation horses on the WAHO website. Spelled Caitni.

What makes me weary of the Ju’aytni = Djeytan association, however, is that Dj in Turkish is not pronounced like J in English/Arabic. Dj in Turkish is more like an “Sh” which gets you far from the strain name.

“Until now” – does that mean that you have uncovered something?

And oof, sure. I suppose there’s always a very, very thin possibility that someone read the word and garbled it from there, but I think it is unlikely that the name was not orally transmitted.

So all in all…Sheitan would be the actual name of Leopard. Sounds like it was already a very popular name for horses at that time 🙂

I like the idea of two different grey “Sheitans”, original imports to Western countries, breeding at the same time but thousand of miles apart (our Cheitan and Leopard) 😀 These boys had frightening names but they managed to made their blood being sought after by generations of breeders so that we can still enjoy their descent today 🙂

Maybe! Kate said she wanted to check some Turkish, Arabic, and English language things before completely ruling it out, though, and I trust her to be reasonably smart about it, what with her doctorate-level schooling in ancient languages and all that haha

Here is my take on this, noting that I am not speaker to Ottoman Turkish: There are two Cs in Ottoman Turkish, a C that is pronounced like “Dj” (or j in jaguar or jelly) hence the rendering Djeytan, and a C with a cedilla, pronounced with like a “Ch” (as in chocolate). It is possible that the horse’s documents confused the two.

I know very little about Turkish, Ottoman or otherwise, but the current Turkish alphabet, based on the Roman alphabet, was only introduced in 1929; in the nineteenth century, it was written in a script derived from Arabic. I’ve been digging through Anglophone grammars and dictionaries of nineteenth century Ottoman Turkish, and comparing them to the modern alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet to get some idea of how the characters and sounds all link up.

What I’ve learned so far is that there was no standardised western transcription for Turkish into the Roman alphabet, and that there are three possible letters in the running for the initial sound in the name transcribed as “Djeytan” (angle brackets are a linguistic convention for indication a written form; square brackets indicate a phonetic form, but I will skip the International Phonetic Alphabet here as being somewhat specialised).

In the modern Turkish alphabet, there are, as Edouard, says two letters that resemble English “c”. The one is written “c” and pronounced the same way as English “j”. The other is the c with the cedilla “ç” (hoping that won’t turn into a block), which is pronounced like English “ch”. The third possible sound is written in modern Turkish as “j” but pronounced like the French “j” or in English the sort of zh-sound in “measure”.

In nineteenth century Anglophone transcriptions of Turkish from the Ottoman Arabic-based alphabet into Roman characters, the first sound, the one now written “c”, is regularly written “dj”, the second “ç” (c with a cedilla) is regularly written “ch”, and the third, now written “j”, is regularly written “zh” in nineteenth century Anglophone texts.

Now, I don’t know how widespread this orthographic practice was, as I know very little about Turkish, let alone nineteenth century conventions for transliterating it. It does suggest to me at the moment that the name written “Djeytan” is a transliteration of a name that would have begun with the modern Turkish “c”; some comparison with nineteenth century Anglophone transliterations of Arabic words include “Djedran”, “Djelfan”, “Djedan” (again, orthographic practice in the nineteenth century is inconsistent, because these may also be found as “Jedran”, “Jadaan”, for instance), which, I am presuming, as I haven’t yet compared them, have the same initial letter (and thus sound?) as “Djeytan”. But I am quite happy to be corrected on this; and besides, this is pure speculation on my part, so take this paragraph with a pinch of salt. It would be interesting to access the Ottoman Turkish records, to see if these horses are listed and by these names, and hopefully settle the matter of pronunciation!

In his 1892/1893 trip to the Middle East Hernan Ayerza commented that in Istanbul they were on their way to see some horses belonging to the mother of the Sultan that had just arrived from Bagdad. So Bagdad seems to had been a rather frequent place from where horses were sent to the Sultan. Completely anecdoticall but the name Sackat or Saekat, bought in 1898, sounds to me somewhat related tor Saktan. I suppose all translation of Arabic names to any other language must be phonetical, so rendered names probably vary significantly among the different writers.

Yes, Arabians for the Sultan came mainly from the province of Bagdad. It does not mean that Bagdad was the source, but rather the main market. The horses came mostly from the Shammar, Montefik and Anazah tribes around there. See Lady Anne Blunt’s comments on that in her “Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates”.

Not for nothing, a friend sent me a photo of Linden Tree that was extracted from the Beatrice Daily Sun, dated August 14 1932, which shows Louis Riesen mounted up on a very pale white stallion identified as Lindentree [sic]. This sent me into the Oklahoma papers archives, and several sources turned up an alternative name for Linden Tree: Ziezefon or Zeizifoun.

Kate turned up https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ziziphus — Zizafun, in Persian.

It’s also the Arabic name for the same plant.