Uncommon strains: Kuhaylan Ibn Mizhir

This is the third feature on the series on uncommon strains, and it features the strain of Kuhaylan ibn Mizhir.

Kuhaylan ibn Mizhir is a little known strain in the West. It is specific to Syria and to parts of Iraq that are adjacent to the Syrian border. The strain belongs to the Bedouin tribe of Tai, who are very proud of it.

The reason it is so little known is that the strain is actually Kuhaylan al-Krush. About eight or ninety years ago, a Tai Bedouin by the name of Ibn Mizhir acquired a Kuhaylat al-Krush from ‘Anazah (either from the Fad’aan or the Sba’ah, and more probably the former), and many in the Tai tribe started calling the strain after its new owner. Other Tai Bedouins stuck to the old Krush strain name.

One of the descendants of this original Kuhaylat Krush of Ibn Mizhir went to the leading clan of the Tai Bedouins, and one of the offspring of this mare then passed to Nuri al-Mash’al al-Jarba of the Shammar, who married a woman from the Tai leading clan.

The Jarba leaders of the Shammar, who took pride in their own Kuhaylan al-Krush marbat (Krush al-Baida, a marbat that came to the Shammar from the Mutayr Bedouins and was from an altogether different Krush line than the Krush of Ibn Mizhir), were reluctant to refer to the mare of Nuri al-Mashal by the strain of Kuhaylan Ibn Mizhir, and reverted to using the older Krush strain.

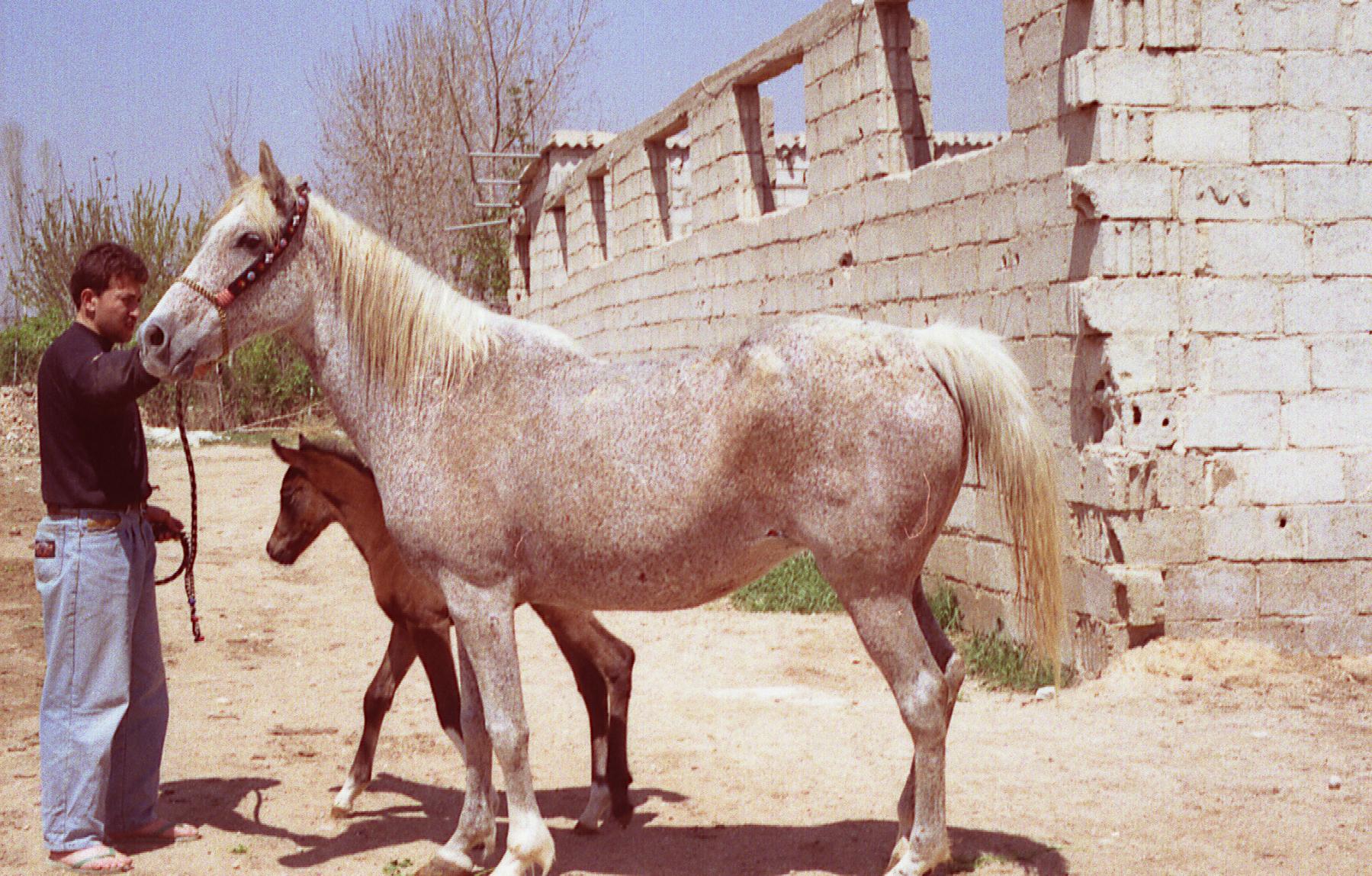

The Kuhaylat al-Krush mare Ghallaieh, whom Aleppo breeder Radwan Shabareq (who told me this story) bought from Rakan, son of Nuri al-Mashal, and Ghallaieh’s daughter ‘Amshet Shammar (photo below) whom I owned, were from these horses. They could be rightly referred to as a Kuhaylat ibn Mizhir as well, even if they were registered as Kuhaylat al-Krush in the Syrian Stubook. Conversely, the Kuhaylat ibn Mizhir horses can correctly be referred to as Kuhaylat al-Krush.

Generally, strain names are fluid and dynamic and they reflect the preferences and choices of the people who used them.

Edouard,

Do you know the DNA? And if so are they consistent as to this group? Or even with the Bahrain Krush?

Jackson

No DNA analysis has been done for these horses yet, and no comparison with other Krush lines.

Amshet Shammar has long legs at the back with very wide and well shaped hocks like Ammoori the son of Ghallaieh with Al aawar

Yes, they look alike a lot, and I believe Ammoori is an excellent desert stallion of the old style

How old is ‘Ashmet Shammar in that photo?

one year. she died at three.

Sorry I mean ‘Amshet Shammar!!

I thought she must be a yearling by her mane and tail, I only asked because of Arnault’s comments re her back legs, she is obviously ‘up at the back’, as we say, at the point this photo was taken as they do grow in uneven spurts, I am sure that she settled into normal proportions as she matured. She had a good depth of girth for a yearling.

I am sorry that she died young.

my father sold her exactly because he thought she was up at the back, and she died a few months later. Her older sister was like this too.

Hello Tina, it is not only a matter of growth, there is an heredity caracter you could see also on his own adult brother Ammoory. It is a matter of habit, at one year old, yourself see, even she is a little bit fat on the photo,that she had a good depth and you could see also she will have large shoulders and hips (Ammoori’s hips are extremly large and shoulders are longs also). I saw also their sister Ebla at Shabareq farm with same nice heredity caracters.

I am glad you said that Edouard, obviously growing horses go through phases of being ‘up at the back’, but I personally would consider being ‘croup high’ in a mature horse as a fault, as is conventional wisdom in our country. I had a horrible feeling that someone was going to say that it was considered a good thing in Arabs!

It actually is a common(ish) fault in Arabs, mildly I don’t think that it is a big problem but it is ugly to my eye and to a marked extent inhibits the horse’s ability to engage the hindlimbs.

On the subject of conformation I read that Deyr was ‘coon footed’,an American term obviously…does it mean toe out.

I am interested in these Davenport horses but obviously there are few,if any here… would anyone be brave/honest enough to tell me the faults that are seen in this line of horses (obviously all groups of horses have their faults as well as merits, I am not being negative just that I have seen few ‘conformation’ shots of these horses so don’t feel able to judge).

Hi Lisa,

“The pastern of the coon-footed horse slopes more than does the anterior surface of the hoof wall, or in other words, the foot and pastern axis is broken at the coronary band”

-ESADinfo.tripod.com

Regarding Deyr being coon-footed, I don’t see it in his photographs.

Carol Mulder, in her Imported Foundation Stock of North American Arabian Horses V1, Revised, says: “In his old age he got a bit soft in the pasterns behind and somewhat too straight in the hocks; these defects were not obvious in his younger days and prime.”

The most important thing in the arabian horse, is the blood, not the fact that he is up at the bak (like Ourour,famous tunisian stallion) or coon footed or toe out etc. Bedouins tell that a good arabian horse, don’t transmit his defaults.

Thanks Jenny, not toe out then as I thought it meant. I am not saying that Deyr was coon footed, I just read that he was.

From the descrpition I think we are talking about a broken forward hoof pastern axis as opposed to a broken back? If by more sloping he means that the hoof wall is nearer the vertical than the pastern. If so it MAY have been due to development issues when he was growing ie contracted tendons. In any case, a bit academic if he was not in fact coon footed!… but at least I know what it means now… thankyou!!

The ‘soft in the pasterns’ bit would have been due to a degree of breakdown of the suspensory ligament as is seen in old broodmares particularly, the hock inevitably straightens in these cases, as I’m sure you know,if he was very old at the time this manifested itself I would forgive it !

Thankyou for the information.

I respect your views Arnault, but based on my experience as a vet working on many Arab studs over many years I would say that conformational faults most certainly are transmitted, not of course to every foal but if the genes coding for that conformation are in a stallions genome, they will be passed on to some of his offspring. Of course there are conformation faults that are develpomental rather than genetic which will not of course pass on; and other conformational ‘faults’ that are actually a matter of taste(ie which don’t really matter to the horse) as opposed to biomechanical weaknesses (which do).

With all due respect, I can’t see how a horse has the capacity to pass on his good points but not his bad…. though I wish that were so it would make horse breeding a lot easier!

We will just have to agree to disagree on this Arnault 🙂

true Lisa, I am not a veto just a breeder and a rider, but don’t forget the blood.

Oh Arnault, it’s not about being a veto, everyone is entitled to their opinion, just that was my experience. You

are right that blood is important, of course.

Like you I think being a rider is important too, I don’t think an Arab horse can be FULLY judged or appreciated unless ridden.. a very beautiful horse may be lazy, clumsy or ungenerous whereas a plainer horse may ride like a dream and give you his whole heart and his last breath… that to me is a good Arab. 🙂