An account of an Indian horse-buying mission to Bagdad in 1907

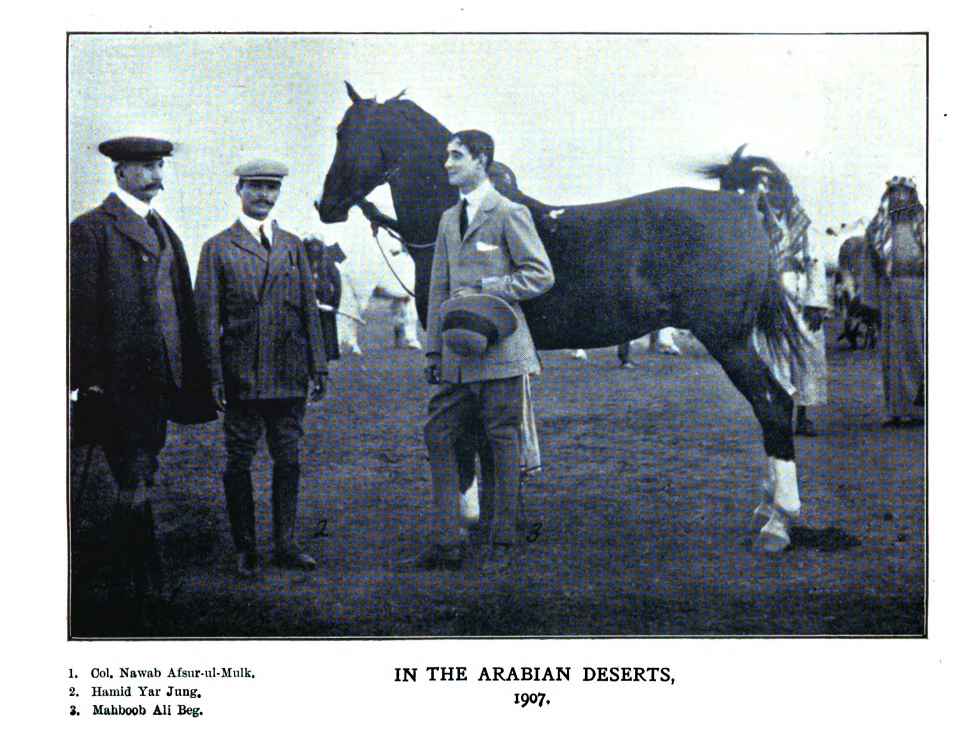

The other day Moira Walker pointed me to the book “A trip to Baghdad: With an Appendix on the Arab Horse” written in 1908 by an Indian senior official, Nawab Hamid Yar Jung. He traveled with his father, Colonel Nawab Afsur-ul-Mulk, and another man, Mahboob Ali Beg, to Baghdad in March 1907, and its vicinity, in search for Arabian horses. The following is the account of his purchase of a chestnut stallion, Faleh:

“My father had seen almost all the horses in Baghdad and had a great desire to purchase a chestnut

of the Nejd breed; but the owner of the horse, who was a wealthy Arab, absolutely refused to part with

it, saying: “You can take any horse you like from this herd, but I cannot allow any of the Saglavi

Jadrania breed to go out of the land, which breed is especially brought up in our clan, and the rest of

the Arabs have not got this kind.”

When my father saw that nothing could persuade the Arab to give up the horse, he could do no better than ask Huzrut Syed Mahamood Effendi (son of Huzrut Nakeeb-ul-Ashraf), who is the religious Preceptor of all the Arab tribes and is held in great esteem by them, to intercede in the matter. So when this Saintly Huzrut went over personally to the owner of the horse and asked him about it, the Arab had no other alternative than to comply.

This was how my father had the opportunity of purchasing the animal for Rs. 2,500. His name is Faleh, and he belongs to the Khyluth-u-thusia Saglavi Jadrania Abbian-us-Sharrak breed. The Arab gave my father the pedigree of Faleh, remarking that this breed had been carefully preserved very long in his family-ever since the days when the Abassides had the Khaliphate of Baghdad.

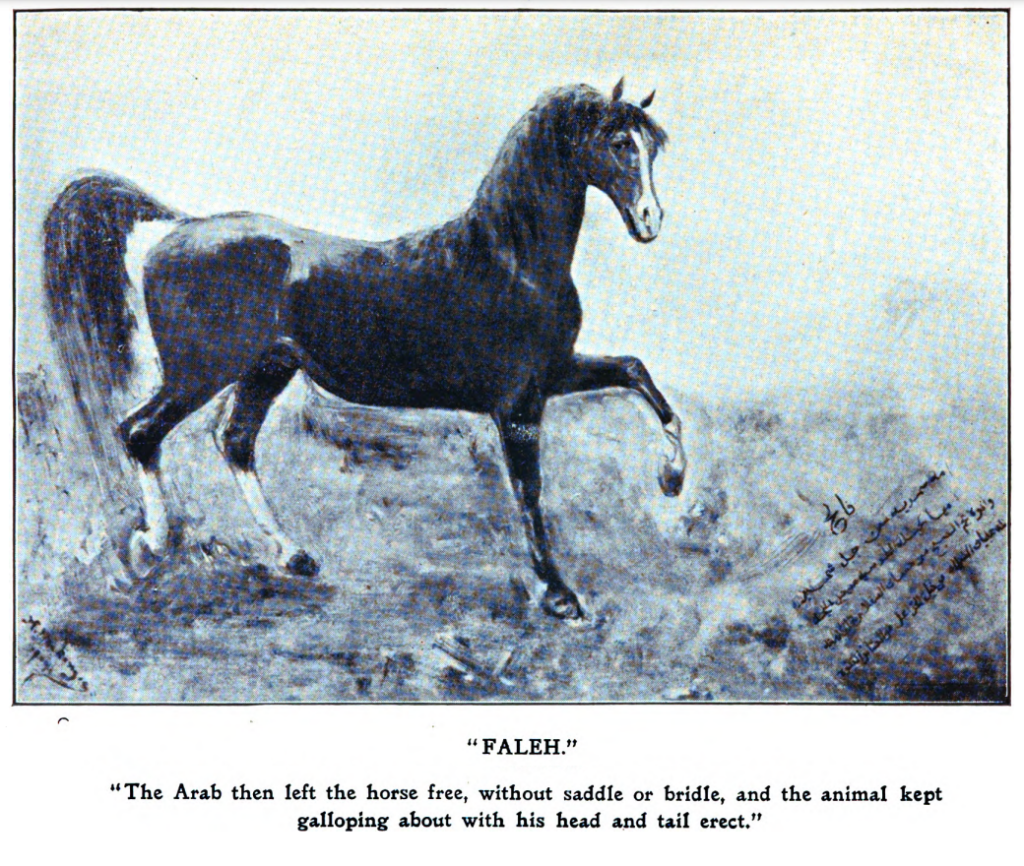

Kate, who also came across this passage, made the good point that the recurrent story about horses’ owners being forced to comply by the foreign buyer (e.g., Homer Davenport with Ahmad al-Hafiz, Major Upton with James Skene) going over their heads could well be a colonial trope to illustrate both how powerful they are and how precious their new acquisition was. Whatever the case, Faleh was a nice horse, as his photo and painting show, below.

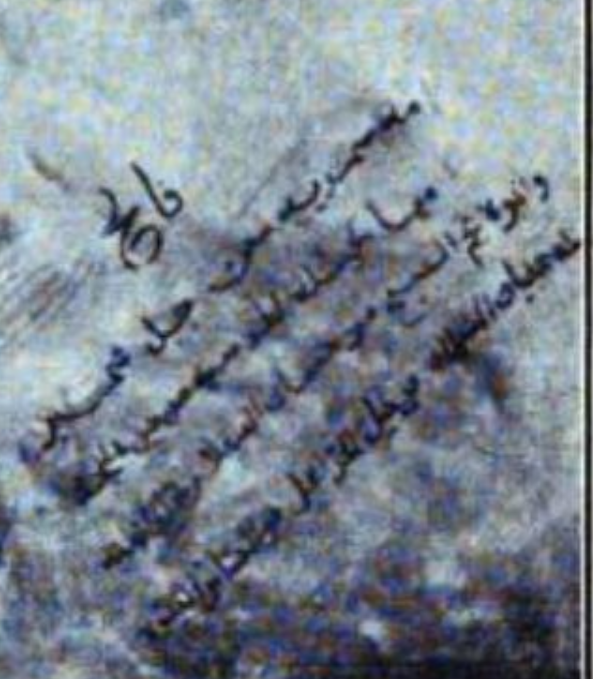

One thing is clear: the buyers were not very familiar with how Arabian horse strains work, because they assigned no less than three strains to their new acquisition. However, a faded annotation in the Arabic language in the lower right corner of Faleh’s painting (see above) provides a clue about his actual strain, i.e., the strain of his dam, and his granddam. It’s a four-line pedigree; the words at the end of each line are illegible. Jeanne Craver helped me enlarged the image of the painting:

My translation follows:

Faleh, his dam is Simriyah from Jabal Shammar, her dam is Kuhaylat al-Tusiyah of the horses of [illegible name of place or tribe]; and his sire is Najm al-Subh [short illegible word] my horse the Saqlawi Jadrani horse, [and the sire] of his dam is Ubayyan al-Sharrak of the horses of al-Khazaa’il of the [illegible name] tribes.

From this it appears that the strain of the horse was Kuhaylan al-Tuwayssah, or Tuwayssan. Tuwayssan is one of the older strains of Arabian horses, as it was already mentioned by the Chevalier D’Arvieux in the 1670s. The mention that it had been preserved by the Bedouin seller’s family since the time the Abbasids held the Caliphate in Bagdad is interesting, because these held the city until the Mongols famously destroyed it in 1258 CE. If true and accurate, it would make Tuwayssan an 850 year old strain.

Finally, the author may have believed that the strain of Faleh was Saqlawi Jadran, perhaps because he thought that Arabian horse strains were passed down from father to son, like for Thoroughbreds. Another explanation is the popularity of the strain with foreigners, so the strain of the sire was attributed to the horse. How could a prominent Indian mission to buy horses and not bring a Saqlawi Jadran back?

The Khaz’ail (plural Khazaa’il) are a branch of the Bani Kaab tribe, in Iran’s Khuzistan today, where an important Arab minority lives, largely from the Bani Lam and the Bani Kaab. The latter had an esteemed strain of Ubayyan Sharrak.

Finally, Kate identified the naqib al-ahraf of Bagdad — the head of the union of the descendants of the Prophet in that city — whose son Mahmood Effendi helped seal the deal with the Arab (i.e., Bedouin) owner of the horse, as Abd al-Rahman al-Kailani. He was later to become the first Prime Minister of Iraq, under the British Mandate:

They also bought another horse: “My father also bought another horse-a very

handsome grey, which belonged to one Saleh bin Sayed and was famous throughout Baghdad.

This horse is of the Aniza Hamdani breed, and is named ” Samer. ” Saleh bin Sayed said that its

brother was sent to Constantinople about two years ago for the Sultan of Turkey.”

The strain of his sire being given to Faleh reminds me of the Ilhami Pasha horses in the French stud book whose sires and dams’ strains were swapped, specifically Naida, Abassie and Aiouf.

I wonder if there are any documents that might corroborate the thirteenth century date for the Tuwayssan strain; would guess that if they exist they would be in Persian or Arabic.

Unfortunately the cities were such documents could be found have been destroyed in the course of the XXst century: Baghdad, Mossul, Aleppo, Homs, and now Gaza. These were the cities where learned urban elites wrote and transmitted information about their assets including horses.

by the way, the name from the strain, Tuwassayh, means “she who has Tuus” (ie., al-Toos, al-Tawss), which is facial beauty.

I love that! Definitely an aesthetic cord stretches from then to today’s Arabians in the West.

As was observed privately, this is also a really interesting find not only because we happened to stumble on several hujaj, but because it’s a rare documented instance where people from the far east went into the desert to acquire Arabians, as opposed to the much more common occurrence of Westerners from Europe and North America.

I really hope someday we’re able to uncover more of the records and activity of the horse buyers from India — there’s a dearth of knowledge there for what appears to have been a fairly active market for Arabian horses.

Yes indeed. Building on that observation, one wonders the extent to which knowledge about Arabian horses among that specific social class in India was influenced by what was known in the UK at that time, or whether there was also an earlier, local body of traditions, or a mix of both. It would be interesting to read the full book.