Follow up on El Emir

For those unfamiliar with the previous El Emir post, I direct you here.

For those having already read the post, I am posting this on behalf of Kate McLachlan and at the request of Jenny Krieg.

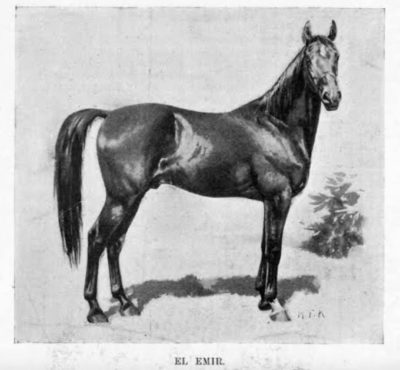

This version of the El Emir photo comes from S. Sidney, “The Book of the Horse”, 3rd edition, 1893. Click on the image for a larger, higher quality view. You can also view the Google Books version here.

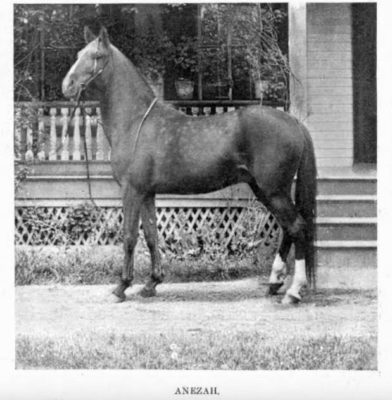

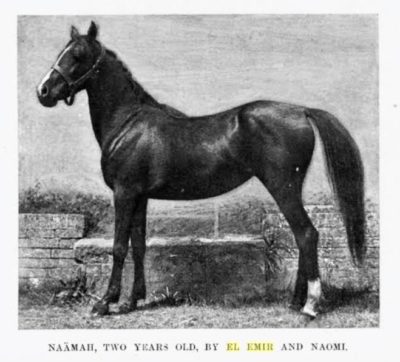

The following horses come from Spencer Borden’s articles on “Ponies and Pony-Breeding” in Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 40, 1896 – which can be seen here. There are also pictures of Maidan and his son Jamrood. The photos are as follows:

El Emir – painting

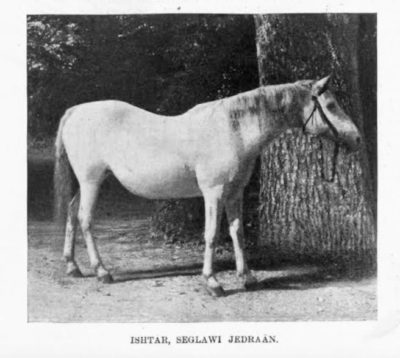

Photo of the mare Ishtar

Anazah (Leopard x Naomi)

Naama (El Emir x Naomi)

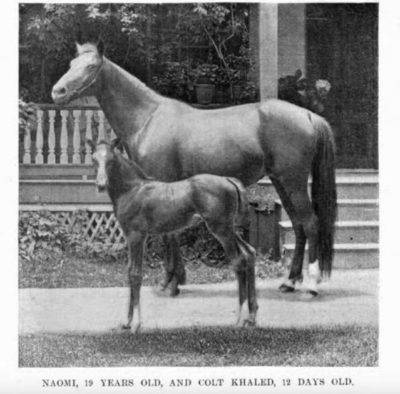

Naomi and her foal Khaled (by Nimr)

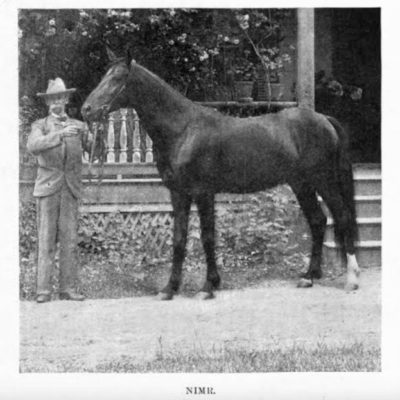

Nimr (Kismet x Nazli)

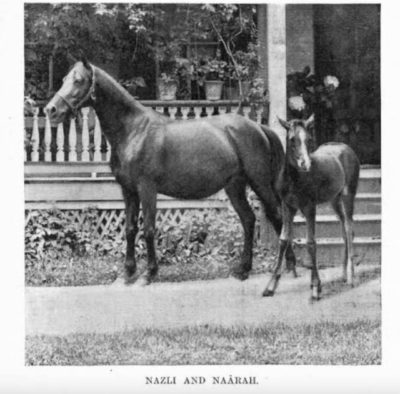

Nazli and her foal Naarah (by Anazah)

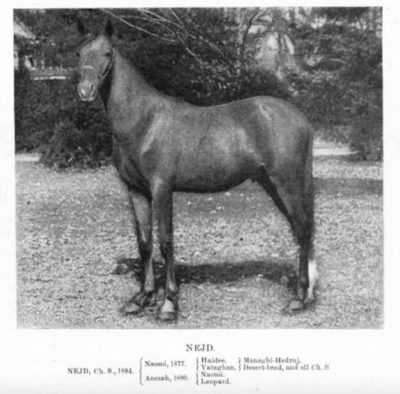

Nejd (Anazah x Naomi)

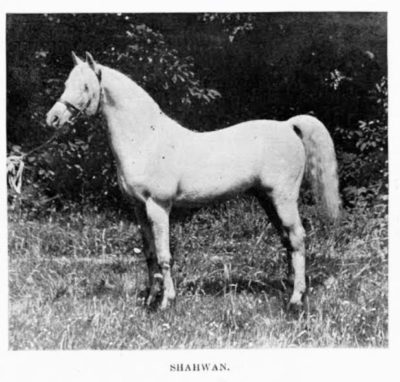

Shahwan

And finally, the photo of Maidan at 23 years of age from Spencer Borden’s The Arab Horse.

Enjoy.

Thank you for this. if you would like to post your recent acquisition of the Wadduda/Muson photo, feel free to do this. RJ Cadranell, Michael Bowling and Jeanne Craver have been trying to figure out who snatched it from the online auction, and they are glad it was you!

Hi Edouard I would like to contact you. We breed Asil SE horses in South Africa and I hear that you are in the country. Could you please email me at the above email. Eugene Geyser

The photo of The Emir has a tremendous resemblance to the french AA that run today as if they were pure Arabs in flat racings.

Is this a new photo of *Shahwan not seen before?

These are just wonderful, especially *Nazli.

Yes, this is a new *Shahwan to the best of my knowledge. Also the only image of Ishtar that I’ve seen or heard of.

I don’t know if it’s a new photo of Shahwan; the photos of Naomi and Nazli certainly aren’t, but quite a few of the other photos were new to me at least, and the Shahwan photo comes from the same series of articles by Borden in the 1896 issues of Harper’s Weekly.

Re: the Naomi and Khaled photo, I’ve actually been able to find a very large, high quality version of it that’s from a source other than Harper’s Weekly. I’ll track that down after I finish looking up a couple of other things.

Yes, here it is: (attempting another XHTML tag) NAOMI AND KHALED, larger

Thank you, Kate and Moira! Great pictures.

It’s indeed sad for El Emir that his one surviving photograph is so unflattering. It does portray his disposition, as he looks interested, yet calm (tail is down). Makes for a dull photo, though. A full mane would have helped. The photo also looks overpainted.

And perhaps his head was more the type one sees in some of the Bahraini horses — not what the modern west would call beautiful, but with plenty of room under the nasal bone to allow for huge expansion of the nostrils. In fact, some horses of the old Shawaf strain in Bahrain were called roman-nosed. But it is an authentic Arabian type!

Dreadfully sorry for posting yet a third time, it only having dawned upon me recently that now I can edit my own comments, but Michael, Edouard, Jeanne, and any others who might be interested: I opted to make a Flickr album to photodump some of the images that I’ve found while mining Google Books for sources. They’re all fit within Early American Arabian, Crabbet, and Davenport parameters – there’s one or maybe two from Boucalt’s Quambi Springs Stud, and a few from Mrs. Eleanor Gates Tully, and I did include a higher quality photo of Shahzada’s sire, Mootrub, simply because the only other version I’ve seen of it was tiny and a little more blurry. I’m sure many are not new, but maybe some are – the Astraled under saddle and this Shahwan photo were, after all! 🙂

—-

And ooooh, yes, Jenny, I was just looking at some of the photos from Mr. Doyle’s visit to the Bahraini the other day and thinking that many of them showed: straight(er) profiles, croups of varying degrees of slope, and a variation of type that ranged from compact little pony Arabian to long, vaguely English Arabian. But, many of the desertbreds seem to have had a rather Thoroughbredy look to them (or perhaps it is the other way around.) One of the Crabbet sires immediately comes to mind – Rataplan.

The pictures of *Naomi and Maidan are familiar, but I have not seen any of the others before. I did not expect ever to see a picture of Ishtar. The *Shahwan picture was apparently taken at the same time as the one on the page linked to below and is every bit as attractive.

http://www.arabianpedigrees.com/crabbet-shahwan.htm

RJ – if either Kate or I turn anything more up on Ishtar, we’ll make sure to let everyone know. She’s one of those confounding mysteries. I have a feeling this photo was taken somewhat late in her career as a broodmare, having been pregnant at least 14 of the 15 years she was actively breeding. I rather like the horse I see in the photo – there’s something very soft about the animal’s demeanor.

Re: the Shahwan photos – my brain is fried, so I’m having a hard time coordinating searching for the date that these photos were taken, unless you’re basing them having been taken at the same time on something else? Could you please clear that up for me? And what of this photo of Shahwan? I’ve seen various versions of it from time to time, but this one is probably the nicest one I’ve run across.

Thanks!

Regarding the two photos of *Shahwan, I’m looking at the foreground, the background, the bridle, the lead line (or longe line), and the length of his tail. It just looks like the two photos came from the same photo session.

As for the *Shahwan photo you linked to, yes, I’ve never seen it with the background so clear. But in this one his tail is longer, the bridle and background are different — obviously this could not have been taken at the same time as the other two.

You do an exhausted pony history nerd great service {laugh} Thank you!

Ishtar would make a good research project. Not only is there a photo of her in circulation now, but also a strain: Seglawi Jedraan. Ishtar’s registration in the General Stud Book does not give any strain information, stating only “A Grey Arabian Mare (foaled in 1871), purchased by Sir W. Clay about the year 1876, and at his death given to Mr Raymond. She is undoubtedly pure bred, but her pedigree has been lost through her frequent changes of ownership.”

However I would be cautious of strain information about Ishtar coming from Spencer Borden. Remember that his 1906 book The Arab Horse states that Ishtar was brought from Arabia by the Blunts, and obviously that’s an error.

The GSB entry does not state that Sir W. Clay imported Ishtar, just that he purchased her. Perhaps he purchased her in England. Sir W. Clay must be the Sir William Dickason Clay who died Nov. 3, 1877 (according to Wikipedia) or Oct. 14, 1876 (according to Modern English Biography).

Maybe there is a record of whether Sir William Clay went abroad in the mid 1870s, and if so where he went. Maybe someone could track down who Mr. Raymond was.

Miss Dillon advertised several stallions at stud for 1894 in vol. 39 of The Livestock Journal. She gives strain information for most of the sires and dams listed, but no strain for Ishtar, Maidan, or El Emir.

https://books.google.com/books?id=Bik_AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA110&dq=Imam+Imamzada+Sohail+Ishtar&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwievK66j7vdAhUk34MKHTbKCDgQ6AEIMzAC#v=onepage&q=Imam%20Imamzada%20Sohail%20Ishtar&f=false

Funnily enough (but perhaps unsurprisingly) both Kate and I are working on Ishtar currently. We’ve tracked down just about all of her offspring, and who owned her after Miss Dillon did, for example. I’ve just sent a letter off to the Clay Baronets, and Kate has been working on the shipping manifests angle for her. If Ishtar was shipped out from somewhere, and shipped in, there will be a record of it, and there may be some identifying information in that record.

And yes, Seglawi Jedraan. It seems like that was THE strain for the Europeans to have at the time, so, I don’t necessarily take it at face value as a matter of principle. Show me hujjah!

There is conflicting information on Ishtar’s strain and importer, and there is really not much on her at all. Sometimes Sir William Dickason Clay is given as the importer (in the year of his death!), and sometimes his brother Sir George, who had served in the Crimean War (and may have seen the Syrian Arabians purchased for the war in action there; there’s an article ‘Horse-dealing in Syria, 1854’, in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Vol 86). As for her strain, Carol Woodbridge Mulder says in her 1969 ‘Foundation Stock of North America’ that Ishtar was a Ma’naqi Sbayli, so make of that what you will!

Mr Raymond is the Reverend John Raymond/Raymund, who bred Ishtar to TB stallions; one of her colts by Colonel Ryan was a racehorse named Oakley. Ishtar landed up with Miss Dillon in 1885, and produced an Anglo-Arab filly Isis by Khamseen that year. After that, she was bred to El Emir and produced the colts Imam, Irak, Ibex and Boanerges between 1886 and 1889.

There are also entries in the Live Stock Journal advertising Ishtar and other Dillon horses at the fifth Crabbet sale, 17 July 1889, and another article whose source I forget giving the results of the sale; Ishtar was sold to Mr Weatherby for 100 guineas. She landed up in the hands of Mr J. Gretton, and produced a black or brown filly by El Emir for him in 1891 at the age of twenty, slipped twins in 1892, and was expecting a foal by Yildiz in 1893 in Vol. 17 of the GSB, though in Vol. 18 (published 1897) it seems she lost that foal as well, or died, as she is recorded as dead.

That is more or less the sum total of my current knowledge on Ishtar, but I am hopeful that with some more digging her pre-1876 history will turn up.

Good luck with it. There must be more information about Ishtar somewhere. There would have been a catalogue printed for the 1889 Crabbet sale, and it should have included an entry for Ishtar, but it might not say any more than what is in GSB. James Fleming, in his chapter on Miss Dillon in the J&C, says that “even Lady Anne” could discover nothing further about Ishtar, but then James doesn’t say how hard Lady Anne really tried.

Come to think of it, James Fleming would have had a copy of the 1889 Crabbet sale catalogue in his possession in the 1980s, but I’d have to see whether that was before or after publication of the J&C.

I’ve been in touch with the people running the Crabbet Heritage archives, and might end up doing some formal research for them if it works out. They have a working page for all of the Crabbet Park Sales (including some very nice pictures), and a large write-up for the 5th Crabbet Sale of 1889. No real information in Ishtar, alas, but they would certainly have the information, and I’m sure if we asked, Mark Tindall would be happy to share with us. He’s currently traveling and wouldn’t be able to access the information atm, but when he gets back in a couple of days, I’ll send him a word about this.

Sir William Dickason Clay’s correct date of death seems to be Oct. 14, 1876, per Oxford Univ. alumni records. He left no children, and his widow, Mariana Emily (Schuster) Dickason, remarried on Nov. 3, 1877, to Arthur Lawrence Haliburton, 1st Baron Haliburton. But there were no children from that marriage, either. One source describes Sir W.D. Clay as “no scholar & no talker, given to guns & horses.”

Well, then, it depends on when Ishtar arrived to British soil, but to my way of thinking, it seems very likely that even if Sir William Clay Bt was the original importer (which… who knows), the brother, Sir George Clay Bt was the person that ultimately handled her.

Yes, the most likely scenario is that either Sir William D. Clay’s widow, or his next younger brother, Sir George, who succeeded him in the baronetcy, gave Ishtar to Mr. Raymond.

I looked up Sir William in the British National Probate Calendar, and for the record, it says:

CLAY, Sir William Dickason, Bart. Effects under L30,000 [nobody else on the page has effects over L9,000, to put that in perspective]. “15 November. The Will of Sir William Dickason Clay late of 9 Lowndes-square in the County of Middlesex and of Castle Hill in the County of Dorset Baronet who died 14 October 1876 at 9 Lowndes-square was proved at the Principal Registry by Dame Mariana Emily Clay of 9 Lowndes-square Widow the Relict the sole Executrix.”

I looked up another in the Probate Calendar, for comparison:

“baroness WENTWORTH the right honourable Anne Isabella Noel of New Buildings-place Southwater Sussex (wife of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt) died 15 December 1917 at Gezira near Cairo Egypt Probate London 14 November to the Public Trustee. Effects L45027 3s. 11d.”

I am not sure that I take your meaning re: the Probate Calendar entries. Care to expound on that?

One more:

“DILLON honourable Ethelred Florence of Villa Cold Eos Cannes France spinster died 17 March 1910 Administration (with Will) London 20 January to Florence Ethel Rosalind Halford spinster. Effects L1124 19s. 11d.”

If I understand your question, my reason for looking at Sir William Clay’s Probate Calendar entry was to see who handled his estate as executor or executrix, his brother or his widow.

The size of the estate is less important, but it shows he had a fairly substantial estate, and to my mind that means there were likely more records made. Perhaps an estate inventory exists somewhere, for example, and perhaps it includes Ishtar.

Oh, that makes a good deal of sense! And it does lend credence to the idea that we would at least be able to uncover a bit more around the circumstances of Ishtar finding her way to Dillon, if not the provenance of the mare herself.

Also it shows that he did leave a will, and a copy of that could be obtained. Probably it does not mention Ishtar specifically, given that he died so soon after he seems to have acquired her, but then again it might say something like “I leave all my horses to my brother George,” or maybe it just says he leaves his entire estate to his wife. We don’t know yet.

I’m coming to this discussion late, but I have seen the photos of Ishtar and *Shahwan referenced above. This is an opportunity to get access to some good copies, and I appreciate that!

I kept meaning to reply to this, but Jeanne – you’d seen this photo before!? Any idea where the version you’d seen earlier came from? I’d love to know if there was another publication source for it.

Also related, in a vague sense as relates to Ishtar and El Emir and some conjecture on the contemporary controversy around them – it just dawned on me that the Dillon family was exceedingly Irish in its roots, and I suppose that that could have factored into the varying levels of disdain the Blunts had for Ethelred’s Arabians, what with certain Victorian and Edwardian models of eugenics taking hold in the realm of science. And in related fashion, does anyone know much about the circumstances of Miss Ethelred Dillon being deaf and crippled? Several references to this have been brought to my attention, but I have yet to see anything explaining that further (and perhaps it never was publicly written about, and so I never shall.)

Read James Fleming’s chapter on Miss Dillon in _Lady Anne Blunt, Journals & Correspondence_.

There is no guarantee that the Miss E Dillon playing tennis in this photo is the horse breeder, but I don’t see anything that would immediately rule it out.

https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/sport-tennis-france-miss-e-dillon-seen-playing-in-the-south-news-photo/79659995

Ambar, probably not. The photo was taken 1906, and Miss Ethelred Dillon was an old woman by that point, having been born in 1838 and died in 1910.

Here I am, once again, commenting on older posts & speculating about horses.

I was closely examining both the photo & painting of El Emir, and I was struck by the differences in markings in both images. Particularly, as I will discuss here, on the head.

The painting shows a horse with a jagged star that comes to a small tapering point at the bottom of the marking which points more towards the left on the forehead. The snip is positioned more along the right nostril; it is long, thin, seemingly not as jagged, and has a slight curve to it. The curve is particularly noticeable towards the bottom of the marking.

Whereas, when we look at the photo, we see a different size & shape of the markings of the horse presented as El Emir.

The photo shows a horse with a much more rounded smooth star that has a longer tapering point at the bottom of the marking, which is angling more towards the right side of the face. The snip is noticeably quite different; it is much larger & wider than what is seen on the painting. As well as being longer & wider as mentioned, the snip is noticeably straighter (not curving as the painting shows), the edges are far more jagged, and the shape is contrasted with that of the horse in the painting.

I can’t say for certain, but I’d expect a horse who is being painted, either by its owner or by a hired artist, would have the markings match much more closely on the canvas to the real life animal compared to what we see here. This is all speculation, but I suspect the photo labelled El Emir might actually indeed be misattributed.

This makes a lot of sense. I don’t know what others think about this.

In the context of the article, there are three paintings, Maidan, Jamrood and El Emir. The paintings of Maidan and Jamrood cannot be of El Emir, as they have completely different markings, so there was no mix-up there. All three paintings are by the same artist, which makes sense, as the three stallions were owned by Ethelred Dillon.

The article is by Spencer Borden, who got the colour of Kouch right, when the General Stud Book did not. He was in correspondence with Miss Dillon, who presumably supplied him with the paintings of El Emir, Maidan and Jamrood, and the photograph of Ishtar for the article. I think it unlikely that Miss Dillon would have sent the wrong images, or mis-labeled them, particularly that of El Emir, whom she adored.

As for the markings, it was common practice to reduce the amount of white on horses in paintings, certainly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The best example of this, off the top of my head, would be the racehorse Eclipse. The portrait of Eclipse by George Stubbs shows a horse with a blaze which ends between his nostrils and white that reaches to just below the hock on his off hind; Francis Sartorius paints him with a similar blaze, but white only reaching halfway up that off hind. The anatomical drawings by Charles Vial de St Bel, who performed the autopsy on Eclipse, however, show that the horse’s blaze actually wrapped around his muzzle and that the white on his hind leg extended above the hock. His markings are more likely to be accurate, as he was not employed to create a tasteful and flattering image of the horse, unlike Stubbs and Sartorius.

White markings are also supposed to have been retouched in photographs as well – belly spots removed, stockings made smaller, etc – because loud white was undesirable.

Essentially, the point of a painting in particular was not to be a faithful representation of a horse in every respect, but catered to the taste of the owner using the conventions of the time. Accuracy in the size and shape of the markings was not generally high on the list of priorities, but deliberate suppression of the extent of white on a horse was. I personally see no reason to suppose that the painting of El Emir would be any other horse than him, given both its source and the fact that paintings are inherently unreliable.

That’s very interesting, I never knew that.

I keep forgetting about the prejudice against white markings and that attitudes have only changed. Admittedly as someone who likes flashy markings, that sort of thing rarely cross my mind.

Regarding retouching, people of the period definitely did it a lot more than we think they did. For themselves and for other subjects in their photos. You learn to look for certain things if you’re aware of it.

I wonder why his markings weren’t touched up more because his sock looks greatly diminished but his head’s markings looks unchanged to my eyes.

Yeah, the photo of El Emir has some very weird retouching. If you look at his back, it appears to have been painted lower, as the planking turns into a solid white line from just about the highest point of his withers, all along his back, and over his croup, with the white stopping just short of his dock. His tail was also fuller at the top, but that was painted out too. His near hind hock has been repainted – I wonder if his tail was obscuring it – and I am squinting at his belly and the background beneath it as well. I don’t know if restoring his back and tail would improve his looks in the photo, but I think it would be interesting.

I definitely think he’d look nicer if someone reversed the edits.

I’m wondering what was the thinking behind lowering his back & making the top of the tail thinner.